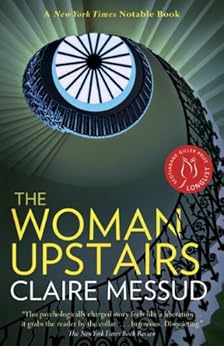

As I mentioned on April 27, I’m featuring some reviews of books featuring nasty women. Today’s review is for The Woman Upstairs by Claire Messud.

3

Stars

Nora

Eldridge, an elementary school teacher and amateur artist, recounts the events

of five years earlier when she was 37 and experienced her “Shahid year.”

Disillusioned with how her life has turned out and feeling “unacknowledged and

unadmired and unthanked,” she lives a life “of quiet desperation” until the

Shahid family arrives from Paris. Reza shows up in her grade three class and

soon she meets his parents: Sirena, an artist gaining fame, and Skandar, a

visiting university professor. The three are glamorous and exotic and worldly,

all the things she has wanted for herself. Nora finds herself wanting “a full

and independent engagement with each of them” though a friend tells her she is

“in love with Sirena but want[s] to fuck her husband and steal her child.” She

soon shares a studio with Sirena, babysits Reza, and has long, philosophical conversations

with Skandar and through them gains a newfound interest in and engagement with

the world. But the three are in Massachusetts for only a year . . .

This is a

psychological portrait of the woman upstairs, “the quiet woman . . . who smiles

brightly in the stairwell with a cheerful greeting” but who “never makes a

sound” and so becomes “completely invisible.” “She’s reliable, and organized,

and she doesn’t cause any trouble.” She’s “so thoughtful of others” but “nobody

thinks of [her] first.” Nora describes herself as all of these, summarizing,

“I’m a good girl. I’m a nice girl. I’m a straight-A, strait-laced, good

daughter, good career girl.” In her art, Nora builds dioramas depicting sad,

lonely and tormented women like Emily Dickinson and Virginia Woolf; these

miniatures obviously reflect how Nora sees her own life.

Everything

changes when Nora meets Sirena who, in contrast, builds grand sculptural and

video-based installations. The problem, of course, is that it is other people

and someone else’s art which are responsible for Nora’s new vitality. Nora is

full of self-doubt and requires outside approval: “If nobody at all could or

would read in me the signs of worthiness – of artistic worth – then how could I

be said to possess them?” She convinces herself that Sirena and Skandar “could

convince me of my substance, of my genius, of the significance of my thoughts

and efforts.” She clarifies, “It’s not right to say that they made me think

more highly of myself; perhaps more accurately, that they allowed me to . . .

My lifelong secret certainty of specialness, my precious, hidden specialness,

was wakened and fed by them.”

A sense of

foreboding permeates the book because it soon becomes clear that her obsession

with the family is unhealthy, especially since her interpretation of Sirena and

Skandar’s words and actions may be based more on her needs and desires than on

reality. Early on, Nora says, “Life is about deciding what matters. It’s about

the fantasy that determines the reality.” This statement raises questions

especially when coupled with Nora’s quoting an Avril Lavigne song: “’You were

everything, everything that I wanted . . . All this time you were pretending.’”

Her descriptions of Sirena are particularly revealing: “If you’re really clever,

like Sirena, then you create a persona – or maybe, more disturbingly, you

become a person – who, while seeming impressively, convincingly to eschew

fakery, is in fact giving people, very consciously, exactly what they want.”

She even decides that a good definition of an artist is “a ruthless person.”

There is no doubt that something happens because she begins her story by

describing her fury: “How angry am I? You don’t want to know. Nobody wants to

know about that.” She ends on the same note: “My anger is prodigious. My anger

is colossus.” Much of the interest of the book is trying to guess what lead to

this “great boil of rage like the sun’s fire” when initially the year with the

Shahids is “paradisiac” and “blissful.”

Many of

Nora’s emotions and desires will resonate with readers. Unfortunately, I found

Nora’s self-absorption and neediness and tendency towards self-pity rather

pathetic. She goes on and on, page after page. In addition, sometimes she is

too willfully blind. For example, she is irked by her aunt: “It had always been

faintly effronting to me, the way Aunt Baby claimed our family lives as if they

were her own.” Yet she doesn’t see the irony of later interpreting Reza’s gift

of a smile “as if he were my own son.” Does confronting one’s mediocrity have

to be tedious?

I

appreciated the many literary allusions, both direct and indirect, and the

book’s examination of the theme of appearance/fantasy and reality, but Nora’s

journey of self-discovery about “the lies [she’d] persistently told [herself] these

many years” is not totally convincing.

No comments:

Post a Comment