Þrístapar was the

site of the last execution in Iceland in 1830.

Two people were executed at that time, one of them being Agnes

Magnúsdóttir. What does this have to do

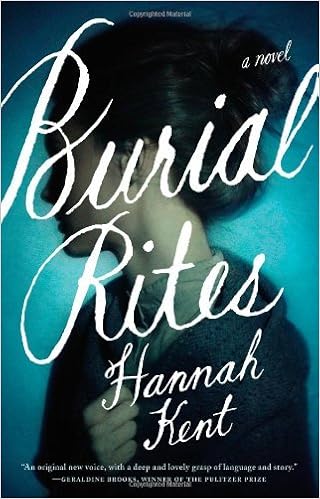

with books and reading? Well, the book Burial Rites by Hannah Kent is a

fictionalized account of the final months in the life of Agnes Magnúsdóttir. I posted my review of the book a couple of

years ago, but I thought I’d repost it.

It is certainly a book worth reading, and it has special meaning for me

now that I’ve visited Iceland.

Review of Burial Rites

4

Stars

This is a

fictionalized account of the final months in the life of Agnes Magnúsdóttir,

the last person to be executed in Iceland. It is 1829 in northwestern Iceland;

Agnes is placed in the custody of a farmer in the months leading up to her

execution. As she awaits her end, she helps with the farm chores and comes to

know the family who are her custodians. She also meets with a clergyman,

Thorvadur “Tóti” Jónsson, who is to serve as her spiritual guide but who

becomes her confidant; it is to him that she relates much of the story of her

“miserable, loveless life” (211).

Agnes

emerges as a fully realized character. There is a great deal of sympathy for

her since her life was nothing but “a dull-eyed cycle of work . . . nothing but

chores, chores, chores . . . the stifling ordinariness of existence” (210).

There is also much to admire about her: intelligence and compassion. She even

shows compassion towards a woman who spreads gossip about her. She is not

perfect, however. Because her life was circumscribed by isolation, loneliness

and abandonment, she naively fell in love with a man who paid her some

attention: “For the first time in my life, someone saw me, and I loved him

because he made me feel I was enough” (210). And she was certainly slow in

realizing the truth about her relationship with this man.

One of the

themes is that truth is not simple and straightforward, but open to

interpretation. Agnes herself claims that there is “’No such thing as truth’”

(105) because different people think different things are important, and for

her, “There is only ever a sense that what is real to me is not real to others”

(106). Agnes tells Tóti “’All my life people have thought I was too clever. . .

.If I was young and simple-minded, do you think everyone would be pointing the

finger at me’” (126). She believes she is not believed because, “’how other

people think of you determines who you are. . . . People around here don’t let

you forget your misdeeds. They think them the only things worth writing down’”

(104).

Agnes tells

Tóti her version of the crime, but it does not tally with what the officials

believe happened. Does she tell him the truth or is the District Commissioner

correct when he says, “’I do not doubt that she has manufactured a life story

in such a way so as to prick your sympathy’” (162)? Does she choose a “young

and inexperienced” churchman believing that she can manipulate him into

appealing her death sentence? Certainly her thought that, “I will have to think

of what to say to him” (97) could suggest forethought and planning.

There is no

doubt that being an audience “to her life’s lonely narrative” (158) influences

the listeners. At the beginning everyone is reluctant to have anything to do

with Agnes; Lauga, the younger daughter, is openly hostile. Margrét fears for

her family’s safety with a murderess in the house, and Jón worries about the

influence Agnes might have on his daughters. Their attitudes change gradually.

Margrét, who initially speaks of Agnes as a murderess and a criminal, later

tells Agnes, “’No one is all bad’” (259) and “’You are not a monster’” (307).

Margrét realizes that her relationship with Agnes has become “more natural and

untroubled” but what is also interesting is that “Margrét worried at this”

(192).

Tóti’s

reaction to Agnes is also interesting. Agnes tells him that they had met years

previously when he had helped her ford a river, yet he “couldn’t remember

meeting a young woman” (78). Later, however, he “thought again of their first

meeting . . . a dark-haired woman preparing to cross the current . . . Her hair

had been damp against her forehead and neck from walking. . . . Then, the

warmth of her body against his chest as they forded the foamy waters on his

mare. The smell of sweat and wild grassing issuing from the back of her neck”

(200). Does he really remember this first meeting?

The Icelandic

setting is almost another character in the narrative. The descriptions of the

harsh climate, the increasing darkness as winter looms, and the barren

landscape certainly reflect Agnes’ feelings of loneliness. There is also no

doubt that such an environment can have an influence on people’s actions. At

one point, Margrét says, “’It’s hard to be alone in winter’’’ (260). As winter

advances so do the reader’s feelings of dread about what will happen to Agnes.

It is

evident that the author did considerable research and she gives a vivid picture

of rural life in Iceland in the early 19th century. I was not aware of the high

level of literacy amongst Icelanders as far back as that time period. The

inclusion of historical documents provides some facts about the case and

stylistic contrast to Agnes’ interior monologues.

There is

much to like about this book. It is not perfect because some of the minor

characters, especially District Commissioner Björn Blöndal, are stereotypes,

but it does have much to recommend it: suspense, a great mystery, a wonderfully

atmospheric setting, and interesting character development.

No comments:

Post a Comment