2.5 Stars

I requested a digital galley of this book because much of it is set on

Grand Manan Island which I’ve visited several times and is one of my favourite

places in Canada.

Despite the book’s title, this is more the story of Esther, Melba’s

daughter, than it is about Melba.

Esther, born in 1954 to an impoverished family on the island, is sent to

live with Melba’s sister Flora and her Jewish husband Sammy in Montreal for ten

years. Then Esther is returned to Melba

until she is 16 and moves to the mainland.

Esther’s adult life, most of it lived near Calgary, is also sketched

in.

The author blurb suggests that in many ways this novel is

autobiographical: “Born into an

impoverished New Brunswick family, Reesa Steinman Brotherton was taken to

Montreal, raised Jewish, then at age 10 sent back to her family of origin.” It seems that the novel is a way for the

author to work through her experiences; it sometimes reads like something

written to help her understand herself.

Esther certainly earns the reader’s sympathy. She is moved around without any consideration

for her feelings; she is, as she repeatedly points out, traded “for a black and

white floor model RCA Victor television set” and later a flush toilet. Melba and Flora’s behaviours are difficult to

forgive, especially because both abandon more than one child.

Yet one can also feel some sympathy for Melba because she is a victim

of poverty. Melba’s husband Russell

drinks excessively and the family home has no bathroom or running water. The community, however, does little to

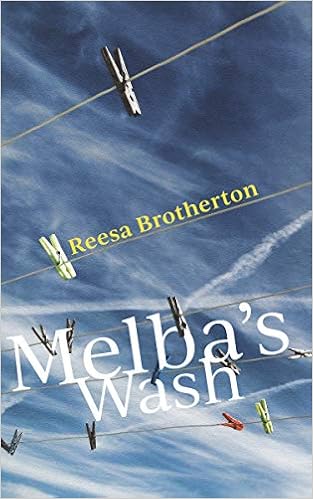

help: “Shame on you Baptists, and

Catholics and Anglicans and Pentecostals.

Didn’t you know that you can tell a lot about a family by looking at the

laundry hanging out on their clothesline?

Didn’t any of you see Melba Girling’s wash? Diapers flying in the salt breeze, greying

and thinning season after season, blue and red, blood stained polka dot

handkerchiefs hanging wrung out of square, patched knees on pants, mended dog-ears

on shirts, and darned, and darned again, work socks.” Melba has a difficult life and seems to have

no friends. It is obvious she longs to

be loved: “Esther had no idea that maybe

Melba needed a friend and that if a person were desperately unhappy enough,

they might not be very choosy about picking him or her.”

Of course, it is not only Melba that suffers. Her daughters look for love and happiness which

they do not have in their childhood home.

Marriage is seen as a way out, but it and the pregnancies that follow

only continue the cycle of poverty. By

the time Frieda, Melba’s oldest daughter, is 24, she has six children and lives

with them and her husband Roger in “a two-room shell of a house” and “No one

knew if Frieda and Roger ever did get off welfare.” Access to birth control would have made such

a difference in the lives of so many women in the novel.

The author’s portrayal of life in the 1950s and 1960s is very

realistic. Esther is born in my birth

year so I can relate to the descriptions of growing up in that time

period. References to ordering from the

Sears catalogue and mixing “the orange egg yolk-looking blob” into margarine

brought back memories. There is even

humour in some of the references: Esther

“didn’t know what we used the Simpson’s catalogues for.”

Esther’s sense of not belonging is nicely emphasized by the repeated

appearance of islands. She is born on an

island and spends ten years on the island of Montreal before returning to Grand

Manan. Even in High River during the flood,

she lives in an apartment surrounded by water. In every home, she feels she is from another

place and doesn’t belong: And “if you

were from away, you could never really belong in the fullest sense of the word,

and you weren’t trusted when it came right down to it.”

Unfortunately, there is too much telling and not enough showing. For instance, it is inevitable that Melba’s

fractured upbringing is going to have an impact on her life. Does the reader really need to be told that

her removal from her secure life in Montreal is the beginning of “the building

anxiety that would last for the rest of

her life”? Her fear of abandonment is unnecessarily

emphasized: Esther “wondered why it was

that she was so bad, what was so wrong with her, that even two mothers didn’t

want her. Esther would wonder this for her whole life.” Esther’s actions clearly show her struggle

with identity, yet the author insists on telling us, “In her mind, Esther lived

between a Christian and Jewish upbringing.

She lived this duality her whole

life.” And we’re told that “Seeds of

doubt, chaos, anger and abandonment, depression and anxiety, pill-taking and

suicide were planted in her short time on Grand Manan, and would follow Esther the rest of her life.” As an adult, “Esther was unhappy. How many times would she have to move? How much money would she have to spend replicating

her childhood home? . . . This road would spread before her for most of her life.”

The majority of the novel focuses on Esther’s life until the age of

seventeen. Then the last 15 percent

covers over 40 years. We are shown

little; we are just repeatedly told that Esther moved again and again and that

she is addicted to prescription drugs.

This last section of the novel needs considerable revision. The detailed description of the High River

flooding is excessive, yet other information is lacking. We learn that Esther’s sister Liona “eloped

with Ross Mackie” but when she reappears she is addressed as Liona Green? A niece that has never been mentioned drives

Esther to pick up her car after the flood?

There is an interesting story here, but the writer’s style needs

polishing. The part of the novel dealing

with Esther’s adulthood needs major revision.

Note: I received a digital

galley of this book from the publisher via NetGalley.