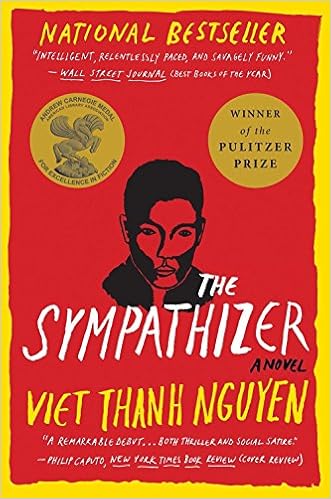

4 Stars

I am not a

reader of spy thrillers or war novels, but this book won the Pulitzer Prize for

Fiction and has appeared on the lists of several literary awards. What I enjoyed the most about the novel is

its social satire.

The

nameless protagonist-narrator is an Americanized Vietnamese with a divided

heart and mind. His narrative takes the

form of a confession written to a Commandant.

It begins in the final days of the Vietnam War when the Americans are

being evacuated from Saigon. The

narrator is an aide-de-camp to the chief of the South Vietnamese secret police,

but he is a Communist undercover agent whose handler is Man, a former classmate

who became a “blood brother”. He becomes

a refuge in Los Angeles but continues as a Viet Cong spy, keeping tabs on other

refugees who are making plans to return to Vietnam and mount a

counter-revolution.

In the

section detailing the narrator’s time in the U.S., social satire comes to the

fore. There are many comments on the

shallowness of American culture. For

example, “America’s most unique architectural contribution to the world [is] a

parking lot.” And “America, land of

supermarkets and superhighways, of supersonic jets and Superman, of supercarriers

and the Super Bowl! . . . Although every country thought itself superior in its

own way, was there ever a country that coined so many ‘super’ terms from the

federal bank of its narcissism . . . ”

The book is

also a satirical look at the promises of the American Dream. There is reference to the “Cyclopean eye of

the IRS” which means that taxation is “a basic tenet of the American

Dream. Not only must [a man] make a living,

he must also pay for it.” Refugees are

“hobbled by their structural function in the American Dream, which was to be so

unhappy as to make other Americans grateful for their happiness.” The refugees may want to assimilate but the

Americans are not easily accepting of them because “all yellow people are

guilty until proven innocent.” The

Vietnamese refugees remain a faceless, voiceless people.

The novel

provides a new perspective on the Vietnam War in contrast to the one provided

by Hollywood. The narrator serves as a

cultural advisor on a film about the war entitled The Hamlet. He wants to give

voice to the Vietnamese characters but “My task was to ensure that the people

scuttling in the background of the film would be real Vietnamese people saying

real Vietnamese things and dressed in real Vietnamese clothing, right before

they died.” It soon becomes obvious that

the author is criticizing the “egomaniacal imagination” of directors like Francis

Ford Coppola who would undoubtedly see a film like Apocalypse Now as “more important than the three or four or six

million dead who composed the real meaning of the war.”

Of course,

there is also a discussion of war and revolution. What is emphasized is the futility of the

Vietnam War for the Americans. And even

for the winners of the war, there is disillusion: “a revolution fought for independence and

freedom could make those things worth

less than nothing.”

This book

is not an easy read. The last section in

particular is difficult with its abundant brutality. The book, however, is a worthwhile read. The sympathizer is often more a spy on

Americans than on the South Vietnamese.

Though he is a Communist sympathizer, he shows that the South Vietnamese

are worthy of sympathy because they were largely abandoned and betrayed by the

Americans. The sympathizer summarizes

what was gained: “I said, Nothing,

nothing, nothing, a grinning simpleton huddled in the corner.”

No comments:

Post a Comment