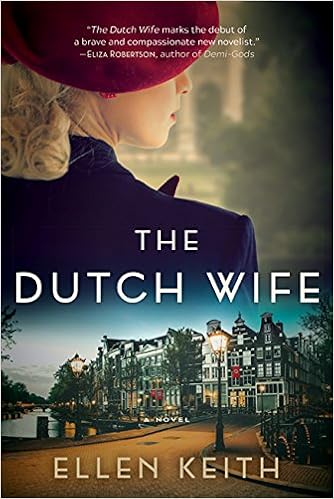

This novel

is narrated from the perspective of three characters. From the first person point of view, we get

the story of Marijke de Graaf, a member of the Dutch resistance, who, along

with her husband, is captured by the Germans.

She chooses to work in a brothel servicing prisoners in the Buchenwald

Concentration Camp because she believes her husband has been interred at that

camp. Then we meet Karl Müller, an SS officer, who encounters Marijke and ends up regularly

seeking her company as a respite from his duties as the second-in-command at

Buchenwald. The third character lives in

a different place and time: Argentina in

1977. Luciano Wagner, a journalism

student, is arrested and becomes one of “the disappeared” during Argentina’s

Dirty War.

As one

would expect given the settings, the subject matter is heavy. Both Marijke and Luciano want to resist

becoming collaborators but also want to survive. Can they be forgiven their choices? Can Karl be forgiven his activities on behalf

of the Reich? The reader sees the

extremes of human beings’ capacity for evil, and the descriptions of prisoner

torture are sometimes graphic.

The author

seems to have done considerable research.

I had read about comfort women, women and girls forced into sexual

slavery by the Imperial Japanese Army in occupied territories before and during

World War II, but I was unaware that the Germans had brothels for non-Jewish

prisoners as a reward for productivity and to create an incentive to

collaborate. Likewise, I knew little

about the treatment of political dissidents during Argentina’s Dirty War.

There are

interesting parallels among the characters and their situations. For example, Karl keeps trying to live up to

his father’s expectations of wartime glory and Luciano struggles to get the

affection of his cold, aloof father. Marijke

describes Karl as someone “trying to be two men at once” just as she sees

herself as conflicted too: “I’d always

taken pride in being sensible and loyal, so who was this stranger who’d betray

all that for something as primal as desire” (205)? Homosexuals are targeted in both places. And then there’s the semblance of ordinary

life found in both prisons: Luciano asks

“But I don’t get how these officers live

on the floor below us. Some have their

wives and children with them. It just

doesn’t – how can they go about their daily lives knowing what surrounds them? .

. . How can anyone eat steak and drink Champagne while we starve overhead in

soiled clothes?” (126 – 127). In

Buchenwald, SS officers live in villas

along with their wives and children, and while the inmates starve, Karl has his

own cook and attends the Kommandant’s cocktail parties and meals where food and

drink are found in abundance.

Some

readers have questioned the realism of the epilogue, but I have more of an

issue with the ending of Marijke’s story.

Given the timeline, her ability to keep the secret from Theo does not

seem credible. Her desire to remain

silent is perfectly understandable, especially after she sees the fate of the moffenhoer (373), but could she really

continue her deception? Initially, I

questioned the ending of Luciano’s narrative, but some cursory research

indicated that what is described did indeed often happen.

The dust

jacket describes the book as “a novel about love” but it is certainly not a

romance. It is more about love versus

lust, love of country, and filial love. It

touches on homosexual love. It also asks

what love can forgive. And in some ways,

the book serves as a warning: this is what

can happen when governments foster discrimination and curb opposition.

No comments:

Post a Comment