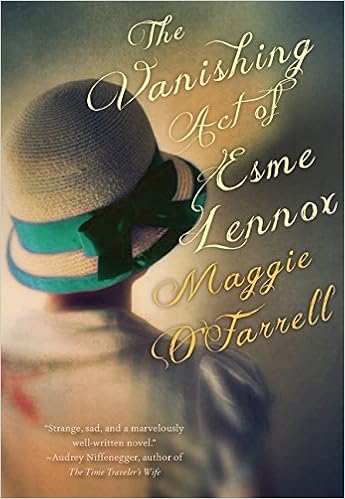

Not too long ago, when I posted reviews of books by Anna Burns and Bernard MacLaverty, two writers from Northern Ireland, a friend suggested I read something by Maggie O’Farrell, another Northern Irish novelist. A bit of research led me to discover that she was nominated for a Costa Book Award three times and won it once. Why have I not read her before?

Esme was born in India into a wealthy Scottish family. After a tragic death in the family, Esme, her

older sister Kitty, and their parents return to Scotland. Esme is a high-spirited, imaginative,

precocious, and irreverent child who often displeases her parents with her disregard

for “rules, these ridiculous rules” of polite society. She

wants advanced education but is denied that so she reads every opportunity she can. After a traumatic event, her behaviour is considered

extreme and she is sent to a mental asylum.

There she stays for over 60 years.

Pending the closure of the asylum, Iris Lockhart, Esme’s great-niece is

contacted. Iris had never heard of Esme

but reluctantly agrees to take her home for a weekend until other accommodation

arrangements can be made. During that

weekend stay, Esme asks to visit Kitty though she is suffering from Alzheimer’s.

The novel reveals how psychiatry was once used to control women who did

not conform. Families were more

concerned about propriety than anything, so women who did not behave demurely

or correctly suffered. Iris does some

research and discovers some reasons why women were admitted to the asylum: “Iris reads of refusals to speak, of unironed

clothes, of arguments with neighbours, of hysteria, of unwashed dishes and

unswept floors, of never wanting marital relations or wanting them too much or

not enough or not in the right way or seeking them elsewhere. Of husbands at the end of their tethers, of

parents unable to understand the women their daughters have become, of fathers

who insist, over and over again, that she used to be such a lovely little

thing. Daughters who just don’t listen.” She learns that “’a man used to be able to

admit his daughter or wife to an asylum with just a signature from a GP. . . .

You could get rid of your wife if you got fed up with her. You could get shot of your daughter if she

wouldn’t do as she was told.’” Esme’s

admission form indicates her problematic behaviour: “Insists

on keeping her hair long . . . Parents report finding her dancing before a mirror,

dressed in her mother’s clothes.”

The narrative structure is interesting.

We learn about Iris and her life – a life which could certainly have had

her placed into an asylum if she had lived sixty years earlier. Then there are flashbacks to Esme’s childhood

and adolescence where the events that led to her admission are revealed. Then there is another voice, that of Kitty,

who speaks in rambling, disjointed passages which show a mind ravaged by

Alzheimer’s and torn by guilt. Her

continual self-justifications suggest that the Edith Wharton quotation in the

epigraph applies to Kitty: “I couldn’t

have my happiness made out of a wrong – an unfairness – to somebody else . . .

What sort of life could we build on such foundations?”

I thoroughly enjoyed this book. It has well-developed characters and an

interesting plot, questions the nature of madness,

and shows how propriety hid a number of crimes.

Anyone who liked The Secret

Scripture by Sebastian Barry should read this one. Esme Lennox is a character who will not soon

vanish from my memory.

No comments:

Post a Comment