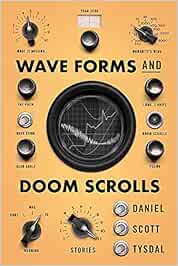

2 Stars

This short story collection was not for me. It irritated me in so many ways.

It is not hyperbole to state that the ten short stories are all over the place. For example, one is about a teenaged fantasist whose intentions are misinterpreted; one consists of waveforms of cinematic scenes; one is about a Holocaust amusement park; and another is an homage to the humanities building at a university.

In one of the stories “The Poem” there’s an editor who pans a poem by commenting, “’it’s like the main point is to make you feel stupid. . . . If you’ve got something to say, just say it!’” This is the way I felt much of the time. The author seems to want to impress the reader. There are allusions to obscure films like “Varda’s The Gleaners and I” and “Ergüven’s Mustang” and “Tarkovsky’s The Mirror” and Kiarostami’s Close-Up.” It may just be a layout issue, but it seems that at the beginning of "Doom Scrolls" a character from Shakespeare’s As You Like It is given a bastardized version of a quotation from A Midsummer Night’s Dream though it is identified as coming from Macbeth? I guess it’s been too long since I earned my degrees in literature!

When I taught creative writing, I would encourage students not to use trite similes and metaphors, but this author seems to go out of his way to be “creative.” The results are sometimes bizarre: “Those emails were the equivalent of trying to quench a baby Gargantua’s thirst for the milk of seventeen thousand, nine hundred and thirteen cows with a SlimFast 3-2-1 Plan Low Carb Diet Ready-to-Drink Shake” and “This feeling sickened the stomach of every cell in me from head to toe.” Similes are piled on similes: “Each time he said it, his eyes widened, as though he had been struck by the name of the thief in a heist flick, by the missing variable of a formula he’d wrestled for years, by the weight of missing years certain amnesiacs must feel while peeling page by page through piles of old photo albums and old diaries and old correspondence from strangers whose status as acquaintance or true friend remains as indeterminate and indefinable as your own reflected face would be if you spent a lifetime staring at the sun.”

Why do so many of the characters feel sensations in the same way: “This smouldering travelled through his hand, up his arm to his shoulder, rising from his neck into his ears, which pulsed with sound, as though a winged-thing’s egg laid there long ago had finally hatched” and “The depth of her skin grew palpable along her arms and neck and back. The sensation made her feel like she was filling with a colony of summer-heated ants” and “she would be overcome by the buzzing up and down her arms of a hive of candle-bearing bees” and “I could feel this body birthing beneath my skin, maturing rapidly from the baby-sized ball of sickness in my gut to a full-fledged nervous system-distending force with a voice” and “Her mother’s strike spreads an electric shiver along the sixteen-year-old girl’s spine and arms, from her shoulders to the hands she clenches to shake it away, a rage-rich burn tightening in her heart and stomach as though the two rulers of her insides are doing battle or trying to fuse into a new, unsustainable organ.”

Lists go on and on: “artists of every ilk – creative non-fiction activists, sober novelists, splatterers of house paints on massive canvases, Hollywood producers with major pull, cynical minimalist poets, guerrilla graffitist, post-country but pre-robotronic steel guitarists, YouTube creators, the composer of mainstream operatic opuses, and on and on and on.” One character goes to the storage room of his apartment building, and for no reason, we are given a description of various storage cages: “Some were empty except for a few weeping cans of interior paints with names like “Roman Ruins,” “Lemon Tart” and “Samba.” Another cage contained nothing but a framed velvet canvas that tackily preserved the wide eyes, pointy breasts and almond skin of a local’s take on a tourist’s vision of a resort-pocked nation’s “fairer sex.” Another was packed with the ghosts of recreations past – golf clubs, tennis racquets, croquet mallets, snorkel gear – while another confined “the replaced” – the replaced microwave, the replaced mini-fridge, the replaced speakers and amp.”

Some passages just don’t make sense: “By the length of its lines, its steady patience in ink, the affable interaction of its infinite internal shapes with the ‘will be,’ ‘was’ and ‘is’ of our saintly, sailing selves, the Poem expressed the manacle-smacking desire to free stuff from its silence, its impermanence, its pseudo-salves and mock healings, all the et ceteras of the sources of impossible vision. It wanted to be the 12-step program to beauty, the thief who snuck truth into the pockets of the masses mobbed by the miserly vitality of ignorance and the inane. The Poem wanted to un-break us. It wanted to be the crazy cowboy who rode us in reverse and made us wild.” Perhaps I’m just not intelligent enough to decipher the meaning.

A pet peeve is an author unnecessarily inserting him/herself into stories. In this collection, the author appears in “Year Zero” and “Dear Adolf” and is undoubtedly the narrator in “Wave Forms.” He teaches at the University of Toronto Scarborough and so ends this collection with “Humanity’s Wing” which focuses on the humanities building at that university, and it’s not difficult to determine which professor represents him.

As I said at the beginning, these stories left me unimpressed and uninspired. Perhaps they’re just too esoteric for me.

No comments:

Post a Comment