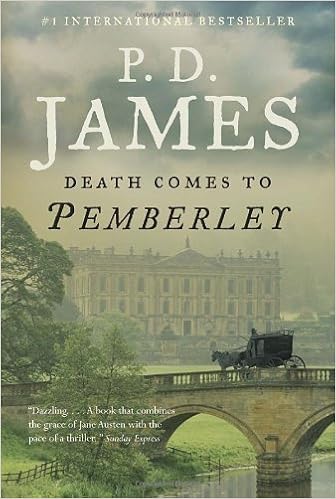

A couple of days ago, I posted about classics being re-imagined as murder mysteries. I suggested that Pride and Prejudice might make a good mystery, but of course P. D. James beat me to it with her Death Comes to Pemberley. I read her spin-off a number of years ago. Here’s my review:

3 Stars

Before I read this book, I re-read Pride and Prejudice because it seemed a great opportunity to

refresh my memory and to enjoy Austen's prose and social satire. Perhaps I

should not have done so because my enjoyment of the mystery was greatly

lessened; reading the two books together served only to emphasize that P. D.

James is not Jane Austen.

Set in 1803, six years after Elizabeth and Darcy's marriage,

the orderly life of Pemberley is disturbed by the unexpected arrival of Lydia

Wickham, Elizabeth's drama queen sister, crying that her husband has been

murdered. It soon becomes clear, however, that Capt. Denny, her husband's

friend, has been killed and the scoundrel Wickham is the suspect. An inquest

and trial follow. The ultimate solution is revealed through a clumsy deus ex

machina: there are several last-minute revelations, including the cliche of a

death-bed confession.

What is least enjoyable about the book is the characters.

Elizabeth, the smart, sharp-tongued character of Austen's novel, has become

dull and self-effacing. She says little and seems concerned only with propriety

and the need to keep up appearances. She is very much a secondary character

because the men soon become the focus.

Gone is the self-assured Darcy. After initially taking

charge of the situation when Lydia appears, he soon becomes befuddled.

Elizabeth and Darcy have become an old, too earnest, too dutiful couple, who

seldom interact, much less exchange the witty banter which endeared them to

Austen's readers.

In addition, other characters do not remain faithful to

their depictions in "Pride and Prejudice." Rev. Collins becomes Mr.

Bennet's nephew, instead of his cousin (3)? Colonel Fitzwilliam does not behave

as Darcy's friend and has become a snob. James does try to offer an explanation

for his change (25, 109), but it's not convincing.

The servants, Mrs. Reynolds in particular, are annoying in

their efficiency. Mrs. Reynolds distributes candles in the hall (99), appears

with water and towels outside the gunroom (101), provides hot soup in the

dining room (105), and ensures there are blankets and pillows in the library

(107). She does all this in a short period of time without the help of staff

whom she ordered to bed to prevent any untoward inquisitiveness (99). James

takes great pains to emphasize that Mrs. Reynolds is invaluable to Elizabeth

and believes that "the family were never to be inconvenienced and were

entitled to expect immaculate service" (20), but the woman can't be

everywhere doing everything.

There are problems with continuity. Darcy somehow manages to

do things he has no time to do. Darcy admits that he and his wife "have

scarcely seen each other" (76) but she somehow manages to warn him about

the conversation Col. Fitzwilliam wants to have about Georgiana (109).

Furthermore, Denny and Wickham have a conversation enroute to Pemberley; this

conversation leads to Denny vacating the chaise. No reader, once he/she learns

the topic of that conversation, will believe that it would be discussed in

front of Lydia, the other passenger in the chaise.

Then there are the anachronisms. Darcy looks at his

wristwatch - about a hundred years before such timepieces came into popular

use. Some of the dialogue uses diction (such as "subconscious")

inappropriate even to the loose approximation of nineteenth-century prose that

James attempts. The references to characters from other of Austen's novels seem

contrived and introduce problems with time elements. James' attempt to appear

to be an Austen expert (by alluding to several of Austen's novels) serves only

to reveal the opposite.

James may have written the book as an homage to Austen, but

it does not succeed. In its dark mood and supernatural elements it is more

reminiscent of Wilkie Collins and Charlotte Bronte. In her author's note, James

even apologizes to Austen because she strongly suspects Austen would disapprove

of her bringing "odious subjects" to Pemberley.

Combining a mystery with a comedy of manners makes an uneasy

mix of genres. The mystery is mediocre with too-obvious clues. Missing is the

sparkle provided by Austen's clever social commentary; as a result, the book

can only be described as lacklustre. Fans of P. D. James may enjoy the book

more than fans of Jane Austen.

No comments:

Post a Comment