3.5 Stars

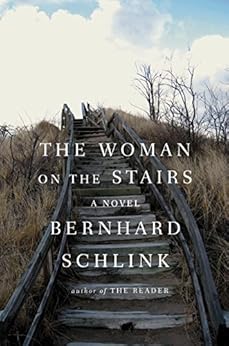

The unnamed

narrator is a corporate lawyer who became involved in a dispute over ownership

of a painting. “Woman on Stairs” is a

nude painting of Irene Gundlach painted by Karl Schwind; it was commissioned by

her wealthy industrialist husband Peter.

Irene left Peter and moved in with Karl.

While serving as Karl’s lawyer, the narrator falls in love with Irene,

and she manipulates him into helping her steal the painting for herself. Forty years later, the narrator comes across

the painting in a gallery in Sydney, Australia, and he tracks her down; he

wants to confront her about how she used him in the past but wasn’t willing to

have a relationship with him.

The unnamed

narrator is a corporate lawyer who became involved in a dispute over ownership

of a painting. “Woman on Stairs” is a

nude painting of Irene Gundlach painted by Karl Schwind; it was commissioned by

her wealthy industrialist husband Peter.

Irene left Peter and moved in with Karl.

While serving as Karl’s lawyer, the narrator falls in love with Irene,

and she manipulates him into helping her steal the painting for herself. Forty years later, the narrator comes across

the painting in a gallery in Sydney, Australia, and he tracks her down; he

wants to confront her about how she used him in the past but wasn’t willing to

have a relationship with him.

His

encounter with Irene results in his examining his past. Through flashbacks, we see how he became

successful and wealthy in his career:

“Now, looking over the past, I have no idea what was a blessing, what a

curse; whether my career was worth the price.”

Security mattered more than anything:

“No, I was not shackled to my life, rather I had chosen it with care,

and held on to it with care. . . . I chose my career out of spite; I married

because there was no good reason not to.

The first decision led to the big law firm; the second, to three

children.”

He led a

dull life of routine: “the years

themselves had become a ritual faithfully adhered to, case by case, client by

client, contract by contract.” He always

did the pragmatic thing; he claims “I take things seriously, sometimes too seriously,

I aim for precision in everything I do, sometimes too much precision: again and again I have difficulty

understanding why people become emotional in difficult situations instead of

solving the problem rationally.’” He is

emotionally stunted; he even refused to share his feelings with his wife,

seeing such sharing as “a ritual of submission.” He seems incapable of sympathy or

empathy: “’The exploited and oppressed –

they have to figure out their problems themselves.’”

Irene

points out that he lived a “walled-in life” and comments, “’I love how keen you

are to trudge from task to task, dutifully doing yet another merger, yet

another acquisition, as if it meant something.’” As a result, the narrator gradually starts to

question his priorities and the choices he made. He wonders whether his wife and children had

been unhappy: “Did I hear no complaint

from them only because we talked so little?

What else was left unsaid?” He

questions the decision he had made to send his children to boarding

school: “Had I really thought that was

what was best for them? Or had I just

given myself an easy and comfortable child-free life?”

Irene is a

foil for the narrator. She is enigmatic;

he is so predictable. She explains that,

unlike him, security was not what she had wanted: “’I was looking for someone . .

. who would take a risk, someone

I could take a risk with.’” She hated

being a trophy wife for Peter, a muse for Karl and a damsel in distress for the

narrator, so she took control of her life and left all of them. The narrator admits, “How courageously she

had lived it; how timidly I had lived mine.”

The novel

examines how one’s life is affected by the choices one makes. Irene took risks and there have been

consequences for some of her past actions, yet she seems content with most of

her choices. Her one regret she tries to

correct. Irene calls the narrator both

“brave knight” and “pure fool”. So late

in life, will be continue to be the latter or become the former?

This is

very much a novel of character. I

enjoyed it though I found the narrator unlikeable. Karl and Peter were also self-absorbed. Why all the men would be infatuated with

Irene is understandable. I was, however,

troubled by Kari the Aboriginal boy who keeps an eye on Irene. He seems like a stereotypical Aboriginal wise

man. What is his purpose? Is he just another male smitten by Irene?

The book

will appeal to readers who don’t mind a slow-paced narrative which focuses on

characters. Though fairly interesting,

it does not carry the emotional impact of Schlink’s The Reader.

No comments:

Post a Comment