Set in the

1830s, this novel, shortlisted for both the Man Booker Prize and the Giller

Prize, covers about eight years in the life of its narrator, George Washington

Black (Wash).

Set in the

1830s, this novel, shortlisted for both the Man Booker Prize and the Giller

Prize, covers about eight years in the life of its narrator, George Washington

Black (Wash).

Wash was

born into slavery on a sugar plantation in Barbados. When he is 11, he is rescued from the

brutality of field work when chosen by Christopher Wilde (Titch), a naturalist

and inventor and the brother of the plantation owner, to be his manservant and

to assist him in his scientific endeavours.

Wash’s intelligence and his aptitude for drawing pique Titch’s interest

so he nurtures his talent and introduces him to the wonders of the natural

world. The death of a man leaves Wash

with a bounty on his head so Titch and Wash flee the island. This is the beginning of Wash’s travels as he

eventually finds himself in far-flung locales as he tries to make his way in a

world, “trying my best . . . to be my own free man” (231).

In some

ways this is an adventure tale. Wash travels

the world: Virginia, the Arctic, Nova

Scotia, London, Amsterdam, and Morocco.

He gets to fly in a hydrogen balloon, sail the sea and dive into its

depths, and see the high Arctic and the desert.

It is also a coming-of-age story showing Wash’s psychological growth from

youth to adulthood. Most importantly, it

asks the question, What is true freedom?

As a child,

Wash asks his surrogate mother, “’What it like, Kit? Free?’” She tells him, “’When you free, you can do

anything. . . . You go wherever it is you wanting. You wake up any time you wanting. When you free . . . someone ask you a

question, you ain’t got to answer. You

ain’t got to finish no job you don’t want to finish’” (9). As a slave, Wash has no freedom; his owner even

takes measures to ensure that his slaves aren’t free to choose death by

suicide. So Wash dreams of freedom,

though Titch warns him, “’Freedom, Wash, is a word with different meanings to

different people’” (154).

When Wash escapes

the plantation and Titch offers him freedom in Upper Canada, Wash admits, “’I

was terrified to my very core, and . . . the idea of embarking on a perilous

journey without Titch filled me with a panic so savage it felt as if I were

being asked to perform some brutal act upon myself, to sever my own throat”

(182). This reaction reveals that Wash

remains a slave; he knows no life but being the property of someone else,

though it upsets him when Titch, to avoid confrontation, tells someone, “’Indeed,

the boy is my property’” (140). In a

telling comment, Titch laments, “’You will never leave me, Wash . . . Even when

I am gone. That is what breaks my heart’”

(216).

Eventually,

Wash must live on his own. Once he is

forced “to leave behind Titch’s coddled world,” he discovers he will never be

free of “the brutality of white men. To

be called nigger and kicked at in disgust like a wharf rat” (231). Though he is technically a free man in Nova

Scotia, he hides from a bounty hunter he fears is looking for him. Though he becomes an accomplished illustrator

and a pioneering zoologist, he cannot get the recognition he has earned: “in the end my name would be nowhere”

(385). At one point, Wash makes a

conclusion that his time with Titch “had schooled me to believe I could leave

all misery behind, I could cast off all violence, outrun a vicious death. I had even begun thinking I’d been born for a

higher purpose, to draw the earth’s bounty, and to invent; I had imagined my

existence a true and rightful part of the natural order. How wrong-headed it had all been. I was a black boy, only – I had no future

before me, and little grace or mercy behind me.

I was nothing, I would die nothing” (165).

Just as Wash

always carries physical scars of his slavery, he can never be truly free of the

psychological trauma of his enslavement.

For example, he has difficulty trusting people; whenever he meets

someone, he remains suspicious: “Despite

his general mildness, I feared him, of course” (80) and “no part of me did

trust him” (177) and “But it is also true that there was something in him I did

not fully trust” (234). After he lives without

Titch in his life, he feels he has no identity because he had one only in

relation to Titch: “I became a boy

without an identity, a walking shadow” (230).

His sense of wonder at the natural world and his sketching of it cover

his fear and loneliness because he remains a lost soul with a “sense of

rootlessness” (400).

Of course,

the concept of freedom is examined through other characters as well. Does Titch’s father stay in the Arctic to be

free of familial ties? Titch is an

abolitionist who believes “Slavery is a moral stain” which “will keep white men

from their heaven” (105), but in order to do his research and create his inventions,

he requires access to money made by the sugar cane plantation where slaves

labour and are inhumanely treated so he can never be truly free of family

duties. Though Titch has more personal freedom than

his family’s slaves, feelings of guilt haunt him, and he is like Wash who

cannot be free of his past. Wash recognizes

that “wounds had arrested [Titch] in boyhood” (416) and because of Titch’s background,

Wash even speculates that perhaps for Titch “any deep acceptance of equality

was impossible” (322).

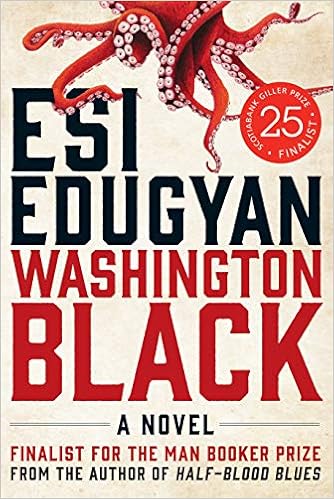

The cover

of my copy has a sketch of an octopus which proves to be a symbol in the

novel. On a diving expedition, Wash

finds an octopus that “swam directly into my hands” (274) and he wishes to keep

it alive and protect it. The octopus is,

of course, an exotic creature, and Wash sees himself as an oddity: “a creature . . . a disfigured black boy with

a scientific turn of mind and a talent on canvas, running, always running, from

the dimmest of shadows” (230-231). When

taken captive, the octopus becomes ill in her tank; “I looked at the octopus,

and I saw not the miraculous animal but my own slow, relentless extinction”

(337-338).

There are

some elements in the novel that irritated me.

For instance, there are quite a few coincidences where people appear

almost magically. Wash’s narration also

bothered me: though he is obviously

intelligent, he is an uneducated boy born into slavery who struggles with

learning to read, yet he has such an extensive vocabulary?

Though not

perfect, this is a book I can see myself re-reading. It has a depth that invites a second look.

No comments:

Post a Comment