4 Stars

This novel focuses on a strong female protagonist, 99-year-old Pauline Sinclair, whom the reader will not soon forget.

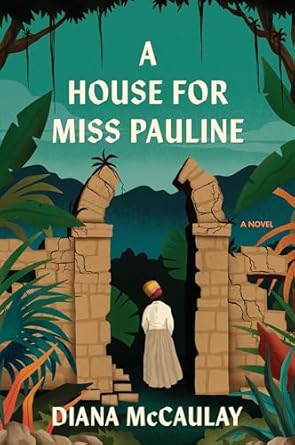

Pauline has spent her entire life in Mason Hall, a rural Jamaican village. She believes she is not long for the world when the stones of her house begin to shift and she hears voices which she thinks are telling her “there’s atonement to be made”: “mebbe me can set tings right before ma time come.” As she considers what she must do, she reflects on her life and so the reader learns about her past. Self-educated, she raised two children with her beloved Clive and supported her family by becoming a ganja farmer. But there are secrets she has kept hidden from everyone and these are the ones she must now reveal to those she feels she has wronged. With the help of her granddaughter Justine and Lamont, a local teenager, she finds these people to make amends but also ends up discovering much she did not know.

It’s impossible not to like Pauline. Fiercely independent, she does not allow anyone to tell her how to live. She understands that many would dismiss her because she can be perceived as “Black, female, old, rural, foreign, poor, powerless, friendless, uneducated,” but she demands the respect she believes she deserves; certainly the last four adjectives do not apply to her. Even as a young girl, she was defiant and took decisive action against a predatory man, leaving a strong message: “That is for me an evry odda girl you ever put you nasty, dutty hand on.” Her life has not been easy, but she persevered and became a community builder and elder. Though not formally educated, she is very intelligent and thoughtful, reflecting on her own actions and on the legacy of slavery in Jamaica.

Though fierce and feisty, there is a softer side to Pauline. Her granddaughter thinks she shares the same hard heart as her grandmother, but Pauline counters, “’Ma heart not hard but ma spine strong. Sometime folks mix up them two tings.’” She does indeed show her heart in her interactions with others, especially in her relationship with Lamont. She sees his vulnerability behind his exterior and virtually adopts him as family. She also has a sense of humour, taking pride in her ability to be as foulmouthed as anyone: “If this man thinks he can win a swearing contest, he’s mistaken.”

The book examines the complex history of colonialism and slavery. Pauline uses stones from the old plantation mansion to build her home and then others in the village do as well. Building homes from the stones enslaved ancestors used to build the backra house is a symbolic reclamation of what was stolen from them and a proclamation that, though the white slave owner is gone, they have survived: “Backra house, the slavery ruin in the forest, where people, her people, her ancestors, toiled and died – no, were murdered – yet became a sanctuary for her.”

Pauline thinks about the meaning of land and its ownership: “Land is what bring the white people here an what mek them capture the Black people an force them clear it an plant it.” She decides that “Home . . . is the land. Not the house. The land will never turn against her.” Land for her is not a commodity; it’s the place that has shaped her identity. But to be at peace she wishes to “settle for herself the question of who owns the land on which her house sits.” Others may have ownership papers for the land but doesn’t her and her ancestors’ intimate and historical connection to the land give her some right to it?

Pauline and other characters speak in Jamaican patwa. This adds realism, but I did sometimes experience some difficulty with some words. I think listening to an audiobook version read by someone familiar with the language would be a good experience.

Note: I received an eARC from the publisher via NetGalley.

No comments:

Post a Comment