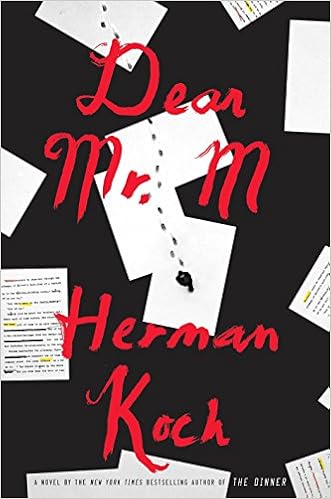

4

Stars

This is a

“literary” thriller: it has a mystery to

be solved but also examines the literary world.

The book

opens with an unnamed narrator (later identified as Herman) stalking his

neighbour, a writer known as M. There is a definite undertone of menace as the

narrator makes statements like “Yes, I have certain plans for you, Mr. M” and

“I’m here, and I won’t be going away, not for a while yet” and “I consider you

a military target” and then proceeds to follow not just the writer but his

family. Gradually, it is revealed that in

his bestselling book, M used events from Herman’s adolescence and distorted

them to create an exciting plot. Using a

highly publicized case involving a teacher, Jan Landzaat, who went missing and

was never found, M distorted events in his fictionalization and basically portrayed

Herman and a friend as killers.

The novel

examines the connection between fact and fiction and the process of creating

and crafting a work of fiction. Does a

writer have the right to appropriate facts and use people as material for

fiction, especially if by rearranging events for the sake of the plot he

negatively impacts the lives of the real-life people involved? Herman certainly wants to exact retribution

because he feels M exploited his life. Authors

observe people and the world around them and inevitably incorporate them in

their work, but should they be allowed to do so with impunity? Writers are taught to eliminate coincidence

because “Coincidence undermines a story’s credibility” and “Coincidence ruins

the credibility of a writer” though “reality is glued together with

coincidence.” What if a coincidence is a

key factor in a real-life event and its omission totally distorts reality? Koch introduces his theme in a

tongue-in-check epigraph: “Anyone who

thinks he recognizes himself or others in one or more characters in this book

is probably right. Amsterdam is a real

city in the Netherlands.”

There is

considerable suspense in the book. Koch

uses a number of techniques to keep tension.

When action reaches a dramatic point, the perspective is abruptly shifted

to a different point of view. The

viewpoints of a number of characters are given, some in first and some in third

person narration, and there are frequent shifts between past and present. There is more than one unreliable narrator so

the reader is left to try and decipher the truth. And, yes, there are unexpected twists in the

plot.

One benefit

of the changing points of view is that the reader’s feelings about a character

change. Herman describes M as a fading,

mediocre writer who is narcissistic and exploitative. When M becomes the narrator and the reader

becomes privy to some of his thoughts and feelings, a more sympathetic picture

emerges. When the opinion of others is

added, like that of M’s wife, another dimension is added. By the end, M is fully developed. The same is the case for Herman; parts of his

personality are described by various people with whom he comes in contact. Flashbacks to his youth help round out his

character.

What is

interesting is how similar M and Herman are.

Herman accuses M of invading his life and stealing it for his purposes,

yet Herman does the same with his video camera.

He photographs people in personally devastating moments, invading their

privacy, and then mocks those people in a public way. There are other similarities: both have troubled pasts, both are jealous of

others who are more successful, and both have mean streaks that occasionally

come to the fore.

One aspect

I really enjoyed is the way characters mock others for things which worry

them. Herman constantly refers to

Landzaat’s long teeth and Landzaat agrees that “his own teeth weren’t exactly

his ace in the hole” but when he thinks of Herman he describes his teeth at

length: “And his teeth! His teeth were too weird to be true. To call them irregular would be putting it

mildly. Those front teeth that curved

inward and the open spaces between his canines and the molars behind made him

look like a mouse more than anything else.

A mouse that had been smacked in the teeth by a much bigger mouse. How could a girl be drawn to that? They were teeth that let the wind through, a

girl’s tongue would have a hard time not getting lost in there.” M is married to a much younger woman and

worries about growing older and being forgotten, yet M and his wife mock N, an

older colleague who always has a young woman on his arm, and M comments that

N’s “countless wrinkles and folds in his cheeks and around his eyes seem to

deepen even further – the landscape of gorges and deep valleys above which the

sun is now doing down.” Koch definitely

knows a lot about human psychology.

Readers who

enjoyed Koch’s previous books The Dinner

and Summer House with Swimming Pool

will certainly enjoy this one. There are

sections that I found a tad tedious – the discussion of Dutch politics and the

changing relationships among Herman’s various friends – but there is much to

recommend this book. Koch is an author

who pokes fun at authors but examines serious issues as well. And provides well-rounded characters and an

entertaining plot that keeps the reader guessing.

Note: I received an ARC of this book from the

publisher via NetGalley.

No comments:

Post a Comment