On this

date in 1950, Edna St. Vincent Millay died.

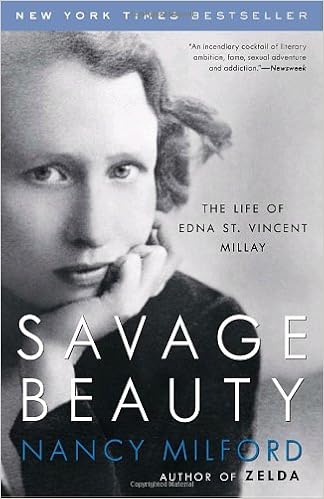

In her honour, I thought I’d post my notes on a biography of her which I

read a number of years ago: Savage Beauty: The Life of Edna St. Vincent Millay by

Nancy Milford. I’m not a biography

reader but I’ve always loved Edna St. Vincent Millay’s sonnets and even own a

first edition of her Collected Sonnets.

In some

ways I wish I hadn’t read the book: the

poet was not always a nice person. I

knew a little about her beforehand: in

the heart of the Depression, her collection of sonnets sold thousands of

copies; she was the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry; she was

the first American figure to rival the frenzy surrounding Lord Byron whose life

and work shocked the public.

The book

discusses the influences of Edna’s mother, Cora Millay, who was very ambitious

for her daughters: “She made [them] –

oh, not ordinary” (9). One observer mentioned

that she had “never come across a more devoted mother and daughter” (176), and

Milford concludes that “the love of [Millay’s] life remained her mother”

(205). Cora saw her daughter’s triumphs

as “part of their triumph” (206). The relationship, however, was not without

its problems: one man noted that Edna’s mother

was “a bit in awe of her. That she had

created such a creature” (234), and the mother wrote that her own indiscretions

might be the cause of Edna’s sexual liberality (237). At times Edna seemed to flee from her mother

but then would feel guilty and would assuage her guilt by sending money (207).

Writing poetry

was the most important thing in Millay’s life.

By 16, she had a sense of vocation (41).

“[Edna] drew people to her . . . [but] her work came first . . . it was

her first love, and perhaps her only one” (130). Milford observes, “people were in some sense

unimportant to her – except as subjects for poems . . . What she was interested

in was her own emotions about them” (199).

In many

ways, Edna was a very selfish and vain person, “the oddest mixture of genius

and childish vanity, open mindedness and blind self-worship” who had “build up

so enormous an image of herself as the Enchanted Little Faery Princess that she

must defend it with her life” (462). “Edna

did exactly what she pleased, when she pleased, and where she pleased” (419),

perhaps unsurprising for a woman who in 1938 was voted one of the ten most

famous women in America (418). She knew “how

to rule a situation or a group” (291), but social approval was very important

to her.

Edna’s life

was anything but orthodox since she had affairs with both men and women. Her promiscuity was well-known in her

circle. Milford suggests that Edna was “irresistibly

drawn to relationships that were doomed to fail. Maybe she couldn’t bear the weight of a

permanent attachment, in which she had no reason to believe” (205) since a

central theme of one of her plays is that the enduring love between women is

the only bond that lasts. Edna flaunted

her sexuality to her mother (234) who aborted her own grandchild when Edna

became pregnant (239).

The one “permanent”

relationship was with her husband, Eugen Jan Boissevain, with whom she had “an

open, free marriage” (351). His devotion

was complete; he even offered to “go and live by himself” (355) and refused to

be “a piece of irritating, dragging piece of family” (357) if he could help

Edna’s extra-marital affair with another man.

Eugen was also sexually involved with other women, and these affairs

were discussed openly by husband and wife” (356). Her lovers knew about Eugen; she wrote one

lover that “I am devoted to my husband.

I love him more deeply than I could ever express, my feeling for him is

in no way changed or diminished since I met you” (305 – 306). Milford even suggests that Eugen “took

morphine so that he would know what it was like for her to be addicted – so that

he would know what she went through trying to stop it” (481).

The

biography was obviously very thoroughly researched. Milford examined numerous documents which are

quoted and cited. She also had the

assistance of Norma, Edna’s surviving sister.

The title is very appropriate: it

describes the audacious poet and the writing of the biographer who spared no

details.

No comments:

Post a Comment