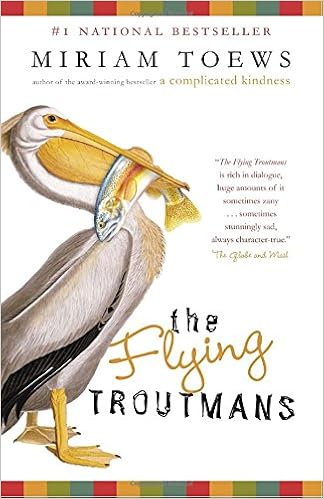

I’ve enjoyed several

of Toews’ novels, especially All My Puny

Sorrows and Women Talking. Somehow I missed The Flying Troutmans which was published ten years ago and won the

Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, so I thought I’d check it out.

I’ve enjoyed several

of Toews’ novels, especially All My Puny

Sorrows and Women Talking. Somehow I missed The Flying Troutmans which was published ten years ago and won the

Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, so I thought I’d check it out.

Hattie Troutman

returns to Manitoba to look after her 15-year-old nephew Logan and 11-year-old

niece Thebes when their mother, Hattie’s older sister Min, has a psychotic

break and is hospitalized. Fearing that

the children will be placed in foster care, Hattie impulsively sets off with

the children on a road trip into the U.S. to find their father Cherkis whom Min

chased away several years ago. As is

typical in road trip novels, they meet their share of quirky characters. Hattie also learns about her two charges and

herself, and because of her reminiscences, the reader learns about the

relationship between Hattie and Min.

It is Logan and Thebes

who steal the show. Logan is a silent

and moody teenager who shoots hoops to relieve stress and carves his thoughts

into the dashboard of the van. Thebes is

a non-stop talker with purple hair and fake tattoos. She never bathes and wears the same clothes

every day. Her obsession is making giant

novelty cheques for people. They are

insightful and precocious, having had to grow up quickly because they’ve been

the ones to look after their mother during her struggles with mental

illness. Though they are certainly odd,

they are also vulnerable. Though the

siblings annoy each other, there is true affection between them, and there is

no doubt that they love their mother.

Hattie is 28 but seems

very immature. She has less insight into

herself than the children have into themselves.

Thebes knows that she’s “on thin ice in the social hierarchy department

. . . not exactly a popular girl” (37), and Logan acknowledges that he feels

very angry at Min’s illness and his father’s abandonment. Hattie, meanwhile, can’t figure out how she

feels about her ex-boyfriend. She

behaves impulsively, the road trip being the best example, and seems to have no

idea about how to care for her nephew and niece. She never encourages Thebes to take a bath,

and Thebes has to tell her to talk to Logan and how to approach him: “You should have a talk with him, said

Thebes. I don’t know what to say, I

said. Well, she said, you could just

start out with talking about how you felt when you were fifteen” (123). Hattie even lets Logan drive, though he doesn’t

have a license.

Hattie’s way of coping

has been to run away. Because she couldn’t

deal with Min’s illness, she “moved to Paris, fled Min’s dark planet for the

City of Lights” (8). The road trip is

just another way to escape: “Anyway I

didn’t want to be here. I didn’t know

how to talk to the kids. I loved them,

but I didn’t want to live with my sister” (27).

Logan has more sense of responsibility than she does; he feels an

obligation to look after his mother and sister.

At one point he asks, “But who would just do that . . . Like, just

leave. You know? Like, just disappear” (127). Hattie’s decision at the end does suggest a

change.

A central question in

the novel is how to help someone who only wants to be helped to die. Several characters suggest that love is the

answer: “we were always meant to be

moving in a love direction, always” (205).

Logan suggests an answer when he discusses how he shoots hoops, always

believing the ball will go into the basket, even after several have not: “I’m always sure the next one will go in”

(242).

No comments:

Post a Comment