I found this psychological thriller to be far-fetched and manipulative.

Saturday, August 29, 2020

Review of THE WIVES by Tarryn Fisher

I found this psychological thriller to be far-fetched and manipulative.

Tuesday, August 25, 2020

Review of FOREST GREEN by Kate Pullinger (New Release)

Friday, August 21, 2020

Review of THE GOOD SON by You-Jeong Jeong

Monday, August 17, 2020

Review of AFTER YOU'D GONE by Maggie O'Farrell

Thursday, August 13, 2020

Review of NOTHING CAN HURT YOU by Nicola Maye Goldberg

Sunday, August 9, 2020

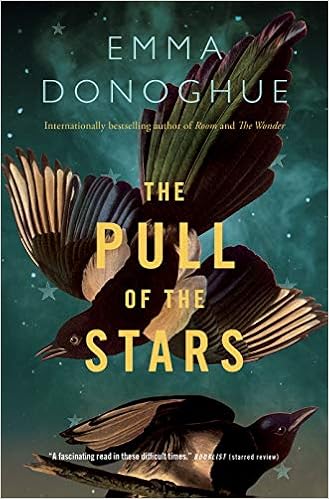

Review of THE PULL OF THE STARS by Emma Donoghue

The narrator is Julia Powers, a nurse working in a Dublin hospital during the 1918 flu pandemic. The events take place over the course of three days (October 31 – November 2) mostly in a supply room which has been converted into a 3-bed maternity ward/delivery room for pregnant women who have the flu. Because the hospital is desperately short-staffed, Julia is assisted by Bridie Sweeney, a young woman with no medical training. Kathleen Lynn - a medical doctor, Sinn Féin supporter, and social justice activist - also comes to help occasionally.

Though the book, written before Covid-19 was declared a pandemic, describes events in 1918, readers living through the Covid-19 pandemic will find much that is uncannily familiar. Schools and shops are closed, people wear masks, and flu victims are “clogging the whole works of the hospital” so there are shortages of medical supplies. There are attempts at social distancing: people waiting for a tram “were far enough apart to be out of coughing range of each other.” Notices offer advice: “The public is urged to stay out of public places such as cafés, theatres, cinemas, and public houses. See only those people one needs to see. Refrain from shaking hands, laughing, or chatting closely together. . . . If in doubt, don’t stir out.”

The plight of women, especially poor women, in Ireland is highlighted: “Always on their feet, these Dublin mothers, scrimping and dishing up for their misters and chisellers, living off the scraps left on plates and gallons of weak black tea. The slums in which they somehow managed to stay alive were as pertinent as pulse or respiratory rate, it seemed to me, but only medical observations were permitted on a chart. So instead of poverty, I’d write malnourishment or debility. As code for too many pregnancies, I might put anaemia, heart strain, bad back, brittle bones, varicose veins, low spirits, incontinence, fistula, torn cervix, or uterine prolapse. There was a saying I’d heard from several patients that struck a chill into my bones: She doesn’t love him unless she gives him twelve. In other countries, women might take discreet measures to avoid this, but in Ireland, such things were not only illegal but unmentionable.” The pandemic has a disproportionate impact on the poor: because the poor are often malnourished, they have little strength to fight the flu. And since the schools are closed, “slum children . . . couldn’t be getting their free dinners there.” Dr. Lynn mentions that the child of a poor woman has “less chance of surviving her first year than a man in the trenches. . . . Infant mortality in Dublin stands at fifteen per cent. . . Such hypocrisy, the way the authorities preach hygiene to people forced to subsist like rats in a sack.”

The treatment of unwanted and illegitimate children in Ireland is emphasized: “Small children did die, poor ones more often than others, and unwanted ones even more than that.” An unwed mother gives birth and Julia wonders what will happen to the child; she assumes the baby will be adopted but Bridie says, “Go into the pipe more likely.” Later she explains, “Mother-and-baby homes, Magdalene laundries, orphanages, . . . Industrial schools, reformatories, prisons . . . aren’t they all sections of the same pipe?”

Birthing is described in explicit detail, so squeamish readers should be forewarned. Nurse Power admires the strength of women who carry the burden of child-bearing and child-raising. An orderly argues that women should not be allowed to vote because they don’t pay the “blood tax” by offering their lives on the battlefields of Europe, but Julia argues tells him, “Look around, Mr. Groyne. This is where every nation draws its first breath. Women have been paying the blood tax since time began.”

The term influenza comes from the Italian “Influenza delle stelle – the influence of the stars” but Julia does not believe in the heavens governing people’s fates. Instead, she wonders about “those who opened their eyes and found they were living in a long nightmare . . . who decreed that . . . or at least allowed it?” Certainly, the lives of the women in the novel seem more ruled by poverty, neglect, and mistreatment than the stars. And there’s a telling question Julia asks at the end when she has to receive the approval of a priest for a decision she has made about the welfare of a child: “who’d put us all in the hands of these old men in the first place”?

The three main characters are all interesting. Bridie Sweeney, though uneducated, is quick to learn and seems caring by nature. A friendship develops between Julia and her assistant, and Bridie describes her life “raised in a home, lodging at a convent.” Mentioned in the Author’s Note is the fact that Dr. Lynn is based on a real person who founded a hospital to provide medical care for impoverished mothers and infants and spent her life advocating for nutrition, housing, and sanitation. Julia changes because she meets Bridie and Dr. Lynn and learns from them.

I wasn’t totally enamoured by the ending which seemed rushed, but I would certainly recommend this novel. It is dark but compelling. I think the author of Room has written another must-read.

Wednesday, August 5, 2020

Review of THE BEAUTY OF YOUR FACE by Sahar Mustafah (New Release)

Afaf Rahman, the daughter of Palestinian immigrants, is the principal of the Muslim Nurrideen School for Girls when a shooter attacks. Interspersed with this plot are many flashbacks to Afaf’s growing up in the suburbs of Chicago. Hers is not an easy childhood or adolescence; she is an outcast at school and finds little solace at home because her family is shattered after a tragic event. Much of her life is spent trying to find her identity and acceptance.

Saturday, August 1, 2020

Review of SEVEN YEARS OF DARKNESS by You-Jeong Jeong

I came across this writer’s name in an article in The Guardian (https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/jun/19/the-best-recent-and-thrillers-review-roundup). I had not heard of her, but she is apparently South Korea’s leading writer of psychological crime and thriller fiction.