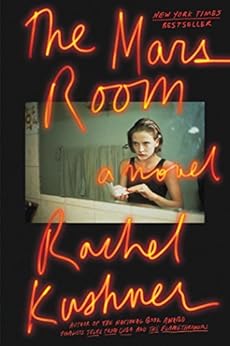

I kept

coming across this title on lists of recommended reads and then found it on the

longlist for the 2018 Booker Prize, so I opted to read it though I’m not a fan

of Orange is the New Black or prison

novels in general.

Set in a

women’s correctional facility in central California, the book focuses on one of

the inmates, Romy Hall, who is serving two consecutive life sentences for

killing a man who stalked her. Through

flashbacks, we learn about her neglectful childhood, the sexual and physical

abuse she suffered, her job as a sex worker, and her drug addiction. We also meet some of her fellow inmates: a woman who killed her own child, a

wisecracking trans woman, a former panty hose model on death row. Two male characters receive some attention: Gordon Hauser, a teacher who takes an

interest in Romy, and Doc, a sociopathic “dirty cop”.

There is no

traditional plot. The book is a series

of vignettes which shift in focus and point of view to tell the stories of

various women: their early lives and

their lives in prison. The realities of

life in prison include punitive rules, inedible food, squabbles between

cliques, and unrelenting boredom.

Everyone engages in smuggling and manipulation to try and make life more

bearable.

The author

emphasizes that socioeconomic factors directly affect the probability of incarceration. Each of the women had limited options from

birth and almost all were victims of poverty, rape, abuse, and exploitation; Gordon

realizes that a person born in poor districts “might be trained from birth

practically to represent your block, your gang, to rep hard, to have pride, to be hard.

Maybe you had a lot of siblings to watch and possibly you knew almost

nobody who had finished school, or worked a stable job. People from your family were in prison, whole

swaths of your community, and it was part of life to eventually go there. So, you were born fucked.” Romy makes much the same point addressing

the reader directly: “You would not have

been wandering lost at midnight at age eleven.

You would have been safe and dry and asleep, at home with your mother

and your father who cared about you and had rules, curfews, expectations. Everything for you would have been

different. But if you were me, you would

have done what I did.” The women

committed crimes of violence but Gordon points out that “there were more

abstract forms [of violence], depriving people of jobs, safe housing, adequate

schools.”

Once

arrested, the women become victims of the justice system. Incompetent and overworked public defenders

fail them. In Romy’s case, for example,

the extenuating circumstances of her crime are never mentioned in court. Once in prison, they are provided counselors: “Counselor doesn’t mean someone who

counsels. Your prison counselor

determines your security classification and when and if you get mainlined to

general population. Your counselor keeps

tabs on you and reports to the parole board, if you are headed for parole.” Romy’s

counselor doesn’t help her find out what has happened to her son; instead, she

says “’Ms. Hall, I know it’s tough, but your situation is due one hundred

percent to choices you made and actions you took.’” What purpose does learning “excellent on-the

job training skills, which would translate into employment upon release” have when

a prisoner has no release date? And

serving long-term sentences seems useless, as Gordon observes: “Gordon could not see that making them suffer

lifelong would accrue to justice. It

added new harm to old.”

The book is

not really an enjoyable read. It tends

to be unfailingly bleak since the women had few choices early in their lives

and now have little hope. The disjointed

structure makes it difficult to connect with the characters though surely the

author wants the reader to do so since her point is that though their existence

is such that one may think of them as aliens on Mars, the women are very much

products of our world. The didactic tone

is also annoying; Gordon, for instance, often seems not much more than a

mouthpiece for the author.

The book is

a strong indictment of the American justice and penal systems and of society as

a whole. It is not, however, worthy of

the Booker Prize for fiction because it often reads more like a work of

non-fiction. Apparently, the author did

extensive research for the book and it shows, but I prefer my novels to be both

thought-provoking and entertaining.

No comments:

Post a Comment