I was

unaware that Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita

was supposedly inspired by a true crime.

In 1948 in Camden, New Jersey, 11-year-old Sally Horner stole a

notebook; the theft was an initiation into a girls’ club she wanted desperately

to join. She was spotted by Frank LaSalle,

a recently released convict whose rap sheet included statutory rape and

enticing a minor. He posed as an F.B.I.

agent who told her she would be arrested if she did not follow his

instructions. He convinced her she must

leave with him to Atlantic City. Thus

began her two-year long kidnapping and serial molestation.

In the

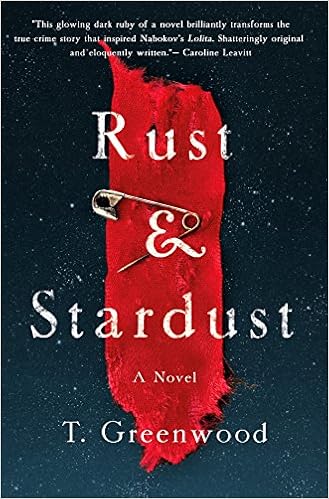

Author’s Note, T. Greenwood states her purpose in writing Rust & Stardust: “While

I drew heavily on Sally’s heartbreaking story, this novel is ultimately an

imagined rendering of the years that she spent on the road with her captor and

of the impact of her abduction on those she encountered along the way as well

as those she left behind.”

The

perspective of a number of people is given.

The focus is on Sally, Ella (Sally’s mother), Susan (Sally’s sister),

and Al (Susan’s husband), but the views of other minor characters, both real

and imagined, are also given. The one person

who is not given a voice is Frank.

The events

depicted occurred 60 years ago when the phrase “stranger danger” did not

exist. I understand that young girls

would have been much more innocent and naïve, but would they be as naïve as

Sally is for so long? Susan finds some

consolation in learning how Frank lured her sister; she feels better knowing

Sally must have been terrified: “Sally

wasn’t a fool, only a scared little girl.”

Though Sally is supposedly an intelligent girl with boundless curiosity

who excels in school, she believes Frank’s fabrications even as they become

more and more ludicrous?

Ella is an

even more problematic character. It is

difficult to have much sympathy for her.

Even in 1948, would a mother send her daughter on a vacation with a man she

meets for the first time when her daughter boards a bus with him? The man is supposedly the father of Sally’s

classmate with whom Sally will be vacationing in Atlantic City, but Ella has

never met this classmate either. Susan

questions her mother’s judgement: “She

tried to understand how it was that her mother had handed her own child off to this

criminal. She’d walked her to the bus

depot, delivered her to him like a gift.

She couldn’t understand how Ella had been so gullible, so stupid.” When Sally’s letters make no reference to her

classmate and only mention activities with the father, shouldn’t Ella start

questioning? Later, Ella even says, “’Sally. I forgive her for what she done with that

man.’” Her treatment of her daughter

once she returns is hard to understand.

Given how consequential her comments to her husband proved to be, one

would expect her to be better able to control her tongue. When Sally expresses a desire to visit the

woman responsible for her rescue, Ella says, “’Of course not . . . What’s the

matter with you, wantin’ to go back there? . . . You’d think you missed it

there. Living in squalor with that

monster. What’s the matter with you?’” Of course Ella suffered, but she is the adult

and should be more concerned about her daughter’s feelings than her own.

There are

issues with Frank’s behaviour. At one

point, he tells Sally, “’Your daddy killed himself rather than spend a minute

more in the house with you and your crippled mama.’” Frank would have known about the suicide of

Sally’s stepfather which had occurred years earlier? Ruth writes letters to Sally though she

suspects they never reach her, “Not if Frank got to them first. Every day that went by without a response,

she became convinced that he was confiscating them. Hiding them from her.” Undoubtedly Frank would have read those

letters, the content of which should have aroused his suspicions, so why would

he believe a later letter from Ruth in which she suggests he and her husband

have a job for him in California?

The book

has too much detail. Thankfully, the

scenes of rape are not graphically depicted, but the book is overly long. There is suspense at the beginning but a

pattern develops and the book drags:

Sally meets someone who suspects there is something wrong but is unable

or unwilling to help so her situation doesn’t change until she meets someone else

who could help her but misses the opportunity to assist, etc. Several of the fictional characters added (e.g.

Sister Mary Katherine and Lena and Doris) seem to have been added solely to

create suspense. Will this person

help? Then there’s the overly dramatic scene

where Frank jumps out of the shower just as Sally is trying to use a

phone. He can hear so clearly through a

closed door with the shower running and moves so quickly that she still has the

handset in her hand?

Since the

author’s purpose is to imagine the impact of Sally’s abduction, why does the

novel continue for so long afterwards?

Do we really need to know what happens to minor characters that are

figments of the author’s imagination?

And the references to luminous stars in each of the last five chapters

are heavy-handed symbolism.

This book

tells a heartbreaking story which is often a harrowing read. The content often left me feeling

uncomfortable. Though the author insists

“this is, in the end, a work of fiction,” I felt that in some ways Sally was

being exploited yet again. I am not in

favour of censorship, but I wonder why not use Lolita as inspiration and write a novel from the perspective of Dolores

Haze and those she encounters?

Note: I received a digital galley of this book from

the publisher via NetGalley.

No comments:

Post a Comment