3.5 Stars

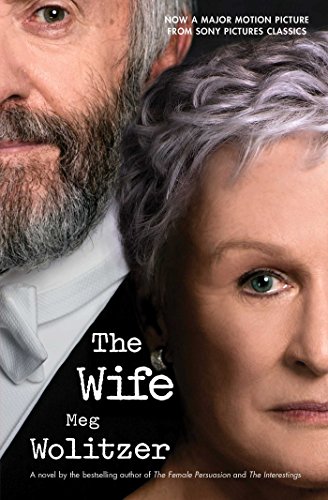

This book

was written 15 years ago, but a film adaptation was released this summer, so I

decided to read the book before seeing the movie.

This book

was written 15 years ago, but a film adaptation was released this summer, so I

decided to read the book before seeing the movie.

Joan and

Joe Castleman are enroute to Helsinki where Joe is to receive a prestigious

literary award. Joan has decided to

leave her husband and plans to inform him of her decision at an opportune

time. In the meantime, she tells the

story of her marriage beginning with their first encounter in 1956. A promising writer, she abandons a career

when she falls in love with her creative writing professor. Joe becomes a successful writer but their marriage

is not always happy: Joe is a serial

philanderer who ignores his children and obsesses about his reputation as a

writer instead. Joe and Joan share a

major secret which the reader learns at the end.

The secret

is not really a surprise because there are so many clues. Besides the obvious hints, what is not said

also serves as a clue. Joan speaks

little about herself and so the reader starts to fill in gaps. Her personality, however, is developed in

detail. She is intelligent but

self-effacing. She lets Joe take the

limelight he so enjoys while she stays in the background and takes on the role

of the supportive wife.

Of course,

Joe’s personality is also revealed. He

is self-centered and vain. His fame has

only bolstered his ego and he constantly yearns for recognition in the form of literary

awards and the adulation of fans. We see

Joe primarily through Joan’s eyes so there may be some bias in her portrayal,

but when he appears, his words and actions confirm her observations. Though he is “one of those men who own the

world” (10), he is a petulant boy “who had no idea of how to take care of

himself or anyone else” (11).

Naturally, Joan’s

role is to take care of him and the family.

As she points out, “Everyone needs a wife; even wives need wives. Wives

tend, they hover. Their ears are twin

sensitive instruments, satellites picking up the slightest scrape of

dissatisfaction. Wives bring broth, we

bring paper clips, we bring ourselves and our pliant, warm bodies. We know just what to say to the men who for

some reason have a great deal of trouble taking consistent care of themselves

or anyone else. ‘Listen,’ we say. ‘Everything will be okay.’ And then, as if our lives depend on it, we

make sure it is” (184).

This is not

the role she initially envisions for herself when she attaches herself to Joe “in

an early fit of girlish optimism” (160) believing that Joe “was the important

one, and I was unfinished. He could

finish me . . . he could provide the things I needed to actually become a whole

person” (63). When she is young and imagines

becoming a writer, she is warned about the sad future for women writers; she is

told emphatically that she won’t be able to get the attention of the men: “’The men who write the reviews, who run the

publishing houses, who edit the papers, the magazines, who decide who gets to

be taken seriously, who gets put up on a pedestal for the rest of their lives.

. . . I guess you could call it a conspiracy to keep the women’s voices hushed

and tiny and the men’s voices loud. .

. . There’s only a handful of women who get anywhere. Short story writers, mostly, as if maybe

women are somehow more acceptable in miniature. . . . But the men with their

big canvases, their big books that try to include everything in them, their big suits, their big voices, are always

rewarded more. They’re the important

ones. And you want to know why? . . . Because they say so’” (53 – 54).

Joan is

given this advice in the 1950s when men did indeed own the world. Things have changed and female writers are

now as common as male writers, but the book provides a look at the recent past

and shows that change has come slowly.

It is not just the fewer opportunities for a career that were a

problem. One of the Castleman daughters

wonders why Joan doesn’t leave the marriage if she’s miserable and Joan

responds with, “She knew nothing about this subculture of women who stayed,

women who couldn’t logically explain their allegiances, who held tight because

it was the thing they felt most comfortable doing . . . She didn’t understand

the luxury of the familiar, the known” (82).

This is an

engaging read. I loved Joan’s acerbic

wit. Her final statement about her

husband may surprise some readers but I interpret it as a way of her taking

control of her narrative. Now I’m off to

see how the film interprets the book.

No comments:

Post a Comment