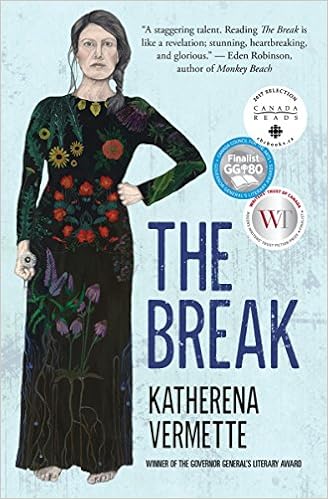

4 Stars

This is one of the finalists for Canada Reads 2017.

In a series

of shifting narratives, the novel explores the aftermath of a violent crime on

a community in Winnipeg's North End. The

book could be called a whodunit (Who attacked the young Indigenous woman?), but

it is much more. The reader does see how

the police investigate the case, but the identity of the perpetrator and the

motive soon become obvious. The focus is

on the effects of the crime on the victim, her relatives (e.g.

great-grandmother, grandmother, mother, aunts, cousin) and her friends. In total, ten different viewpoints are given;

except for the Métis police officer leading the

investigation, the voices are those of women.

This is a

compelling read though not an easy one.

It is the first book I have encountered which has had a trigger

warning: “This book is about recovering

and healing from violence. Contains

scenes of sexual and physical violence, and depictions of vicarious trauma.”

This is a

very timely novel. Statistics show that

Indigenous women are three times more likely to be victims of violence than

non-Aboriginal women, and the Canadian government has launched a National Inquiry

into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. Virtually all the women in the novel have

experienced sexual abuse and/or domestic violence and/or addiction and/or

cultural loss and/or family fracturing.

These are such common experiences as to be almost inevitable. The title refers to a piece of undeveloped land

in the middle of the community which becomes the scene of a crime, but it also

refers to broken people, broken relationships, and broken links with the

past.

Besides a

novel about the difficult lives of urban Native women, this is a book about

resilience and survival. The message is

that women need to support each other to give each other the strength to

survive. It is the connection to family

and the love for one’s family which allow for healing and provide the assurance

that “Everything will be okay.” Stella

has distanced herself from her family but when she re-connects, she feels so

comforted that she doesn’t’ want to leave.

The eldest speaker says, “I know I have my people. I can feel them, even when they go away. It means so much to have people. It is everything.”

Of course,

not everyone has a supportive, caring network.

Phoenix, for example, has no one except an uncle, an ex-con,

drug-dealing gang leader. Her mother

Elsie was gang-raped when she was a teenager and became a drug addict, losing

her three children to the child welfare system.

Phoenix’s behaviour therefore becomes understandable and the reader

cannot but feel some sympathy for her.

The added tragedy is that the dysfunction will continue into the next

generation.

The number

of characters is a weakness. Some

(Phoenix and Stella) are well-developed, but others (Cheryl, Louisa, and

Paulina) are not sufficiently differentiated.

A family tree is provided but the number of nicknames adds to the

confusion: Cheryl is sometimes Cher;

Louisa is sometimes Lou; Lorraine is sometimes Rain; Zegwan is Zig and Ziggy; Alex

is Bishop and Ship, etc. Why does

everyone’s name have to be reduced to one syllable? Phoen?!

The use of Paul for Paulina is particularly annoying because of its

gender confusion. The connections

between non-familial characters are sometimes difficult to keep straight (Stella→Elsie→Phoenix→Cedar-Sage→Louisa→Rita→Zegwan→Emily).

Men in the novel

are not portrayed very positively. Young

Native men are gang members and older Native men retreat into the bush: three of the major characters have been

abandoned by husbands. Absentee fathers

for Native children seem to be the norm.

Only three white men make an appearance.

One is Officer Christie, a stereotypical doughnut-loving cop who is lazy

and bigoted. Jeff and Pete, partners of

Indigenous women, remain flat characters.

The book

does not offer excuses or assign blame; it just shows the situation and lets

readers draw conclusions as to responsibility.

We know that the plight of Aboriginals is a consequence of colonization

by whites, but this is not explored. Neither is the role of residential

schools. However, the racism encountered

by Aboriginals in the health care system and among police is shown. The novel’s achievement is putting a human

face to issues that are often misunderstood.

This book

is unflinching in its gaze at life for contemporary Indigenous women in urban

Canada. It is certainly a book Canadians

should read.

No comments:

Post a Comment