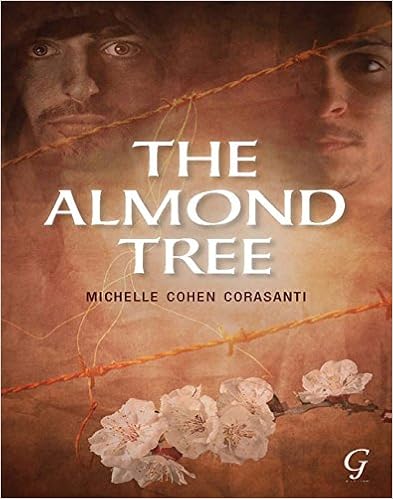

Review of The Almond Tree by Michelle Cohen

Corasanti

1

Star

I looked

forward to reading this book because of the subject matter; unfortunately, the

novel was disappointing.

The book is

the fictional memoir of a Palestinian named Ichmad Hamid. Covering the years

from 1955 to 2009, the focus is on the extreme suffering of Ichmad’s large

family at the hands of the Israeli occupiers. Crisis follows crisis, although

Ichmad is able to better his life because of his intelligence.

A major

problem is the weak characterization. Ichmad’s portrayal is unrealistic as

evidenced in the repeated references to his exceptional abilities. From the

beginning Ichmad sees himself as different: “I knew from a young age that I

wasn’t like the other boys in my village” (14). He is “promoted by three

grades” (19) and, because he becomes a backgammon champion, he becomes “a

welcome and honoured guest . . . sort of a legend” (19) at the village tea

house. His father speaks of his eldest son’s “extraordinary mathematical mind”

(30) and his mother calls him “’my masterpiece’” (31). The village teacher

speaks of him as a genius (112) who will make his people proud (69). Despite

his limited education because he has to go to work to help support his family,

he aces a mathematics competition, graduates at the top of his class (198), and

in his research makes “tremendous progress” (263). And he is nominated for a

Nobel Prize “each of the last ten years” (338)!

To make

matters worse, Ichmad is exceptional in other ways. Twice he is a hero:

“[W]ithout fear,” he rescues a girl from a rabid jackal (80), and later he

saves two students from a fire (197-198). Twice it is mentioned that he works

“around the clock” (196, 289). His generosity knows no bounds: he buys his

nephews convertible Mercedes (324) and pays for the university education of

seventeen nieces and nephews. In his sixties, his body is “firm and strong from

years of running” (317), though not once is reference made to his running to

stay in shape.

Character

transformations are also incredible. A man “well known for his . . . dislike of

Arabs” (137) who may have beaten and arrested Ichmad’s father (159) becomes

Ichmad’s “closest friend” (344)? He is not the only one to undergo such a

miraculous change. When Ichmad first meets Yasmine, he says that everything

about her “screamed ignorance. Her veil, her thick, unplucked eyebrows, her

traditional robe. . . . Her teeth were yellow and were crooked and she was

plump” (271). She has “a ready array of excuses” (276) to not adapt to her new

life in the United States, but later she is described as wearing “tight black

trousers” (305) and having earned a “master’s degree in elementary education”

(310).

And then

there are the gaps and inconsistencies. Abbas “can barely walk” (253) yet twice

he travels a considerable distance to find his brother Ichmad (154, 187), and

both times he knows exactly where to find him at different locations on the

university campus. The village teacher tells Ichmad, “’If you win, I’ll find

jobs for your brothers in my cousin’s moving company’” (110), yet he doesn’t

keep his promise when his prize pupil wins the mathematics competition? A woman

is described as wearing a “lacy undergarment that conformed perfectly to the

round fullness of her breasts” (235), but she never wore bras (278)? A family

agrees not to tell a man about the death of his daughter “until he was

released” (57). When he is released fourteen years later, his first words to

his family are about the death of the daughter (207). When was he told? A

professor accuses Ichmad of cheating. A classmate, without ever being told

about the accusation, comments that the professor has become lazy (163). That

classmate “’figured out what happened’” (174), but the reader is never told how

Ichmad is cleared.

The writing

style is repetitious. When surprised, characters stare “with their mouths open”

(118). On the same page, another person is described: “His mouth was open”

(118). A classmate’s “mouth gaped open” (147) in awe at Ichmad’s skills at

backgammon. His brother stares at him “open-mouthed” (189). And the protagonist

stares with “mouth agape” (186). When Ichmad first sees a woman, she is

described as “the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen” (79) or “the loveliest

girl I’d ever seen” (218). Dialogue is unnatural. Why would Ichmad have to tell

his brother, who was there, “’Don’t forget, everything we owned was destroyed’”

(77) or that the Jews “’control over ninety per cent of the land’” (81)? Then

there are the lengthy advanced math problems (117 – 118, 139, 201) which serve

virtually no purpose in a work of fiction.

Symbolism

is simplistic. The almond tree and olive trees at the back of Ichmad’s family

home are the major symbols. Ichmad says, “They reminded me of my people. . . .

I’d marveled that despite their exposure to beatings, arid landscape and fierce

heat, the trees survived and bore new fruit year after year, century after

century. I knew their strength lay in their roots which were so deep that even

if the trees were cut down, they survived and sent forth shoots to create new

generations. I always believed that my people’s strength, like the olive

trees’, lay in our roots” (207 – 208). The symbol should speak for itself; it

should not need to be explained.

There is no

doubt that the author is passionate about the Palestine-Israel conflict.

Certainly, the Palestinian perspective needs to be given, and to have a Jewish

American attempt to do so is daring. It is unfortunate that the skills required

to write a good novel are missing.

No comments:

Post a Comment