See http://lithub.com/10-college-courses-to-read-along-with-this-semester-from-your-couch/

for the complete article.

Ranked a Top Canadian Book BlogSubstack: @doreenyakabuski

Twitter: @DCYakabuski

Facebook: Doreen Yakabuski

Instagram: doreenyakabuski

Threads: doreenyakabuski Bluesky: @dcyakabuski.bsky.social

Saturday, September 30, 2017

Literary Courses

It’s the

end of September and one month of the school year has come to an end. On the topic of education, I found an article

on Literary Hub entitled “10 College

Courses to Read Along With This Semester (From Your Couch)” by Emily Temple. She outlines ten classes being taught this

fall and the books you’ll need to vicariously read along with them.

Friday, September 29, 2017

Archival Review: THE LOST HIGHWAY by David Adams Richards

Yesterday,

I posted about the appointment of acclaimed author David Adams Richards to the

Canadian Senate. I referred to my reviews

of three of his novels, but I thought I’d add one from my archives in honour of

Mr. Richards’s appointment.

This story

of greed and lost moral focus is a study of what happens when moral questions

become matters of life and death.

This story

of greed and lost moral focus is a study of what happens when moral questions

become matters of life and death.

4

Stars

This story

of greed and lost moral focus is a study of what happens when moral questions

become matters of life and death.

This story

of greed and lost moral focus is a study of what happens when moral questions

become matters of life and death.

Alex

Chapman, a sometime-academic, considers himself an intellectual, a good man who

believes he’s had much bad luck and suffering through no fault of his own. He has quarreled most of his adult life with

his great-uncle James, and when Alex learns James has a $13 million winning

lottery ticket, he sets up a scheme to steal it.

Alex is not

a likeable character. He is full of

self-pity and, though he teaches a course in ethics, his own moral system is

revealed to be very shallow. The reader

may have some sympathy for him as his past is revealed, but eventually the

impulse is to yell at him to grow up. It

is his deluded ego and his actions that lock him into his ultimate fate. There are flashes of goodness in him, flashes

of recognition that he could be so much more than he is. The question which creates suspense

throughout is whether the ethics that Alex has long pretended to embrace will

eventually cause him to take a stand.

Alex’s

alter ego is Leo Bourque, a truly odious individual. Alex enlists Leo to help him swindle his

uncle out of the lottery ticket, but Alex ends up being totally manipulated by

Leo. Alex has mastered the ability to

rationalize any moral position but Leo takes him into moral territory even Alex

is unequipped to handle.

A weakness

of the novel is the author’s hammering home of moral and spiritual truths he

feels modern secular man has forgotten.

There is a repetitive mockery of intellectuals and lectures about how

non-believers inspired by reason rather than faith will become lost souls.

Thursday, September 28, 2017

SENATOR David Adams Richards

I was

thrilled to learn that one of my favourite Canadian authors, David Adams

Richards, has been appointed to the Senate by Prime Minister Justin

Trudeau. He is one of only a handful of

authors who has received a Governor General's Award in both the non-fiction and

fiction categories. He was also a winner

of the prestigious Giller Prize in 2000 for Mercy

Among the Children. See http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/david-adams-richards-appointed-senate-1.4268244

for more information about his appointment.

Mercy Among the Children is one of my favourites of his, but

River of the Brokenhearted and Incidents in the Life of Markus Paul

also earned 5 stars from me.

I’ve already

posted reviews of three of Richards’s books:

Principles to Live By:

http://schatjesshelves.blogspot.ca/2016/06/review-of-principles-to-live-by-by.html

Crimes Against my Brother:

http://schatjesshelves.blogspot.ca/2016/12/canadian-book-advent-calendar-day-18-r.html

Incidents in the Life of Markus Paul:

http://schatjesshelves.blogspot.ca/2015/07/from-schatjes-reviews-archive-incidents.html

Wednesday, September 27, 2017

Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize Finalists

This morning, the Writers’ Trust of Canada revealed the

finalists for the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, recognizing writers of

the year’s best novel or short story collection.

There are five finalists:

Carleigh Baker for Bad

Endings

Claire Cameron for The

Last Neanderthal

David Chariandy for

Brother

Omar El Akkad for American

War

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson for This Accident of Being Lost

The prizewinner, who will receive $50,000, will be announced

on November 14.

Tuesday, September 26, 2017

Latin in English

The

Invictus Games, in which wounded, injured or sick armed services personnel compete

in a variety of sports, are happening in Toronto this week. A friend, who knew I had studied Latin in

high school, asked what “invictus” meant and wondered why Prince Harry had

chosen a Latin word when he founded the games. (I was pleased to be able to answer that the

word meant “undefeated” or “unconquered,” though I don’t know why the Latin

word was used.)

That conversation began a discussion about the utility of Latin. I studied it in high school many years ago; I still have my textbook: Latin for Canadian Schools by David Breslove and Arthur G. Hooper. By the time I became a high school teacher (in a school whose motto is Sapientia omni vincit), Latin was no longer taught, though a colleague and I used to have lunch-time seminars for interested students; the focus was on Latin’s English vocabulary-building potential. Certainly, there are a lot of Latin phrases which have become part of everyday usage: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Latin_phrases_(full).

That conversation began a discussion about the utility of Latin. I studied it in high school many years ago; I still have my textbook: Latin for Canadian Schools by David Breslove and Arthur G. Hooper. By the time I became a high school teacher (in a school whose motto is Sapientia omni vincit), Latin was no longer taught, though a colleague and I used to have lunch-time seminars for interested students; the focus was on Latin’s English vocabulary-building potential. Certainly, there are a lot of Latin phrases which have become part of everyday usage: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Latin_phrases_(full).

I don’t know how many secondary schools offer courses

in the language. A nephew who is

studying to be a priest has been learning Latin because it remains the official

language of the Catholic Church. When he

has asked questions about Latin, I’ve enjoyed revisiting the language.

As a result, I was intrigued by an article in The Paris Review. In “’Human Life Is

Punishment,’ and Other Pleasures of Studying Latin,” Frankie Thomas muses about

the joys and pains of studying Latin: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2017/09/21/human-life-is-punishment-on-the-pleasures-of-studying-latin/.

Latin is not dead; it is alive and well and

living in English.

Monday, September 25, 2017

Banned Books Week

This week (Sept.

24 – 30) in the United States is Banned Books Week. “Banned Books Week is an annual event

celebrating the freedom to read. Typically

held during the last week of September, it highlights the value of free and

open access to information. Banned Books

Week brings together the entire book community — librarians, booksellers,

publishers, journalists, teachers, and readers — in shared support of the

freedom to seek and express ideas, even those some consider unorthodox or

unpopular” (http://www.ala.org/advocacy/bbooks).

To continue

to raise awareness about the harms of censorship and the freedom to read, the

American Library Association publishes an annual list of the Top Ten Most

Challenged Books. Go to http://www.ala.org/advocacy/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/top10

to see the annual lists.

And here are "16 Quotes from Great Authors for Banned Books Week" courtesy of Signature: http://www.signature-reads.com/2017/09/16-quotes-from-great-authors-for-banned-books-week/?cdi=321A47B09DAD4547E0534FD66B0AE227&ref=PRH24BB520913.

Celebrate your freedom to read by reading a challenged book!

And here are "16 Quotes from Great Authors for Banned Books Week" courtesy of Signature: http://www.signature-reads.com/2017/09/16-quotes-from-great-authors-for-banned-books-week/?cdi=321A47B09DAD4547E0534FD66B0AE227&ref=PRH24BB520913.

Celebrate your freedom to read by reading a challenged book!

Sunday, September 24, 2017

Brontë Family Facts

On this date, in 1848, Patrick Branwell, the least well

known Brontë,

died. Patrick Branwell was born on June

26, 1817. Known as Branwell, he was a painter, writer and casual worker. He

became addicted to alcohol and laudanum and died at Haworth at the age of 31.

I thought it was an appropriate date on which to share an

article I read in The Telegraph entitled “11 things you

didn't know about the Brontës”: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/books/authors/11-things-you-didnt-know-about-the-brontes/.

And for some fun, why not try a quiz to determine which

Brontë

sibling you would be: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/books/authors/quiz-which-bronte-are-you/. Apparently, I would be Anne, the least famous of the sisters.

Saturday, September 23, 2017

Essential Reference Texts

A while back, The

Millions asked the following question:

“In the age of Google and Wikipedia, reference books may seem

anachronistic, but some have not been superseded by the internet in their

usefulness and convenience and even in their ability to divert and entertain. What is the one reference book you couldn’t

live without?” (http://themillions.com/2009/04/millions-quiz-essential-reference_14.html)

I’d find it difficult to choose just one, but I’ve narrowed

it down to a dozen that appear on my shelves:

Oxford English

Dictionary; I’ve got the two-volume compact edition with the magnifying

glass.

Merriam-Webster

Encyclopedia of Literature

Benet's Reader's

Encyclopedia by Bruce Murphy

A Glossary of Literary

Terms by M.H. Abrams

Masterpieces of World

Literature in Digest Form, edited by Frank N. Magill

The Oxford Companion

to the English Language, edited by Tom McArthur

The Reader’s

Encyclopedia of Shakespeare, edited by Oscar James Campbell

Chambers Biographical

Dictionary, edited by Magnus Magnusson

The Dictionary of

Cultural Literacy by E. D. Hirsch

The Dictionary of

Classical, Biblical, and Literary Allusions by Abraham H. Lass

McGraw-Hill Handbook

of English Grammar and Usage by Mark Lester and Larry Beason

The Little, Brown Book

of Anecdotes by Clifton Fadiman

Friday, September 22, 2017

2017 Kirkus Prize Finalists

On

September 10, I posted about the longlist of the Kirkus Prize for Fiction: https://schatjesshelves.blogspot.ca/2017/09/2017-kirkus-prize-longlist.html. That list of 423 titles has been narrowed

down to six:

What it Means When a Man Falls from the Sky by Lesley Nneka Arimah

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid

White Tears by Hari Kunzru

Her Bodies and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado

The Ninth Hour by Alice McDermott

Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward

For further

information about the books, go to https://www.kirkusreviews.com/prize/2017/finalists/fiction/.

In the

Young People’s Literature category, three Canadians are on the shortlist. Métis author Cherie Dimaline, who is from

Ontario's Georgian Bay Métis community, is nominated for her novel The Marrow Thieves, which takes place in

a dystopian future where Indigenous people are hunted and harvested for their

bone marrow. The other Canadians include

Guatemalan-born author and translator Elisa Amado for her work on the Jairo

Buitrago-authored children's book Walk

With Me, and Hull, Que.-based translator Madeleine Stratford for her work

on picture book Me Tall, You Small by

German author Lilli L'Arronge. See the

complete list at https://www.kirkusreviews.com/prize/2017/finalists/young-readers/.

The

finalists for non-fiction have also been announced: https://www.kirkusreviews.com/prize/2017/finalists/nonfiction/.

The winners,

who will receive $50,000 US ($60,795 Cdn), will be announced on Nov. 2,

2017.

Thursday, September 21, 2017

Happy Birthday, Stephen King!

Seventy

years ago today, in Portland, Maine, one of America’s most successful authors, Stephen King,

was born. If the books written under the pseudonym Richard

Bachman are included, King has written almost 70 books! (I love that King chose this pen name because

he was a fan of the Canadian rock band, Bachman Turner Overdrive!)

Literary Hub has an article in which twelve writers discuss how King influenced their writing: http://lithub.com/12-literary-writers-on-stephen-kings-influence/.

For the

official list of Stephen King’s novels, go to http://stephenking.com/library/novel/.

And in five days, fans can pick up his

latest book, written with his son Owen, Sleeping

Beauties.

King’s

website gives a short description: “In a

future so real and near it might be now, something happens when women go to

sleep; they become shrouded in a cocoon-like gauze. If they are awakened, if

the gauze wrapping their bodies is disturbed or violated, the women become

feral and spectacularly violent; and while they sleep they go to another

place. The men of our world are

abandoned, left to their increasingly primal devices. One woman, however, the

mysterious Evie, is immune to the blessing or curse of the sleeping disease. Is

Evie a medical anomaly to be studied? Or is she a demon who must be slain?” (http://stephenking.com/p/sleeping-beauties/)

In honour

of the prolific author’s special day, BookRiot

featured an article entitled

“70 Great

Stephen King Quotes on His 70th Birthday” by Liberty Hardy: https://bookriot.com/2017/09/21/stephen-king-quotes/?utm_source=Sailthru&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=The%20Riot%20Rundown&utm_term=BookRiot_TheRiotRundown_Tue-Thur.

Literary Hub has an article in which twelve writers discuss how King influenced their writing: http://lithub.com/12-literary-writers-on-stephen-kings-influence/.

Happy

birthday, Mr. King!

Wednesday, September 20, 2017

Shania Twain: An Inspiration to a Writer

The other

day I read a piece whose title “How Shania Twain Made Me a Writer” by Emily

Yahr caught my attention: http://lithub.com/how-shania-twain-made-me-a-writer/. It’s one of the essays included in a book Woman Walk the Line: How the Women in

Country Music Changed Our Lives, edited by Holly Gleason, which is being

released today.

In the

essay, Yahr, a reporter for The Washington Post, writes that as a grade 8

student in 1999, she was asked to write an essay about someone she

admired. She chose Shania Twain: “I will always admire the woman who put

everything before her career. Who never gave up no matter how bad it was. Who’s

[sic] songs tell the basics of life. Who everyone should strive to be like. Who

is more than just a voice. Shania Twain.”

Yahr’s

article piqued my interest because back in the early 1980s I taught Shania

Twain in Grade 12 English at Timmins High & Vocational School. Of course I knew her as Eileen Twain. I love to tell people that my husband and I

chose a song by one of my students for our first dance; “Forever and For

Always” is the song we first danced to at our wedding.

I was a

feminist even when Shania was a student so I like to think I inspired her in

some of her views. For that reason, I

loved another article written about her:

https://www.theodysseyonline.com/shania-twain-underrated-feminist-queen.

Who knows, perhaps I did.

Regardless,

I hope Shania reads Yahr’s essay. To be

told one has been an inspiration is a great gift.

Tuesday, September 19, 2017

Review of THE SCARRED WOMAN by Jussi Adler-Olsen (New Release)

3.5 Stars

This is the seventh novel of the Department Q series. Carl Mørck, head of the cold case department, sets out to find a connection between the recent murder of an elderly woman and the similar murder of a young teacher a decade earlier. Then there are a series of hit-and-run murders targeting young women, some of whom turn out to be connected to these two victims. All of these cases have Carl and his two partners, Assad and Gordon, working overtime, especially when their assistant, Rose Knudsen, ends up in a psychiatric hospital because of major mental health problems.

As this

plot summary suggests, the plot is very complex with various connections

between the cases being investigated.

There’s a very tangled web that needs to be unraveled. Sometimes there are almost too many

connections; for instance, Rose’s relationship with one woman seems too

coincidental.

The quirky

cast of characters I met in the previous books continues to keep my

interest. There’s good-hearted but

cantankerous Carl, mysterious Assad, and heart-broken Gordon. In many ways, of course, this is Rose’s

book. Throughout the series, there have

been hints that Rose has a fragile psyche; in this book, the full explanation

is given for her behaviour in the past. The

author should be commended for his sensitive treatment of mental illness.

Rose is a

scarred woman, but she is certainly not the only one; it could be said that there

is a Danish det kolde bord of

irreparably wounded women, some of whom have become morally bankrupt if not downright

murderous. Admirable female characters

are a minority in this book. Of course

murderers may also be victims; it is for this reason that I found myself having

sympathy for one killer.

One of the

many women we come to know is Anneli, a social worker, who early in the book

reveals that she thinks people who are non-contributing members of society and take

advantage of social services should be punished. The motives for her actions are

understandable, but her constant laughter turns her into a comic figure: she “laughed manically and unashamedly” and “She

laughed at how well things were going” and she was “laughing at the thought”

and “Anneli couldn’t help laughing insanely at how perfect her plan was” and “Anneli

laughed. It seemed like she had gotten

away with this” and “Never before had she laughed so much with relief” and “Am I going crazy? she thought and

started to laugh again. It was all so

comical and fantastic” and “She laughed at the thought” and “She burst out

laughing at the thought” and “She laughed again, holding the half-empty glass”

and “She lay on her side on the sofa, doubled up with laughter cramps.”

As in the

other books in the series, there are humourous touches. The banter between the

members of the department continues.

Assad’s misuse of idiomatic expressions is one source of amusement. A scene involving a car thief’s first attempt

at stealing a vehicle is hilarious.

Comic relief is needed because there is a lot of murder and mayhem

throughout.

The novel

is narrated in third person from multiple points of view including Carl’s and

that of both victims and perpetrators.

At times the reader has to guess at the identity of a killer and at

other times he/she knows who the killer is and wonders when/how the killer will

be apprehended. At the beginning, there

are switches in time period that can be confusing; the book moves from April 26

to May 13 to May 2 to May 11.

Fortunately, chronological order becomes the norm as the narrative

progresses.

I would

definitely recommend that readers begin at the beginning of the series. The previous six books describe the

personalities of the recurring characters, explain the relationships among the

various characters, and outline the specific issues faced by individuals. For example, if one knows the details of Carl

and Mona’s relationship, Carl’s uncomfortable encounters with Mona in this book

are understandable. As well, the reason

for Carl’s having a paraplegic roommate is explained in the earlier books. I read somewhere that three more books are

planned for this series. Presumably one

of them will focus on Assad’s background.

I am

looking forward to the next Department Q installment. If you have not already discovered this

Danish mystery series, do check it out, beginning with The Keeper of Lost Causes.

Note: I received an eARC of this book from the publisher via NetGalley.

Monday, September 18, 2017

2017 Scotiabank Giller Prize Longlist

The 2017

Scotiabank Giller Prize jury announced its longlist today. There are 12 titles:

David

Chariandy for Brother

Rachel Cusk

for Transit

David

Demchuk for The Bone Mother

Joel Thomas

Hynes for We’ll All Be Burnt in Our Beds

Some Night

Andrée A.

Michaud for Boundary

Josip

Novakovich for Tumbleweed

Ed

O’Loughlin for Minds of Winter

Zoey Leigh

Peterson for Next Year, For Sure

Michael

Redhill for Bellevue Square

Eden

Robinson for Son of a Trickster

Deborah

Willis for The Dark and Other Love

Stories

Michelle

Winters for I Am a Truck

The

shortlist for the richest fiction prize in Canada ($100,000) will be revealed in

Toronto on Monday, October 2, and the winner will be announced on November 20.

For more

information, go to http://www.scotiabankgillerprize.ca/2017-longlist/.

Sunday, September 17, 2017

Review of THE LAST POLICEMAN by Ben H. Winters

3.5 Stars

Maia, a

gigantic asteroid, is approaching and will collide with Earth on October

3. Though its point of impact is

unknown, the asteroid is so large that its collision will have planet-wide

effects; much, if not all, of the world’s population will be killed. Governments have enacted strict new emergency

laws as societal structures start to fall apart.

Maia, a

gigantic asteroid, is approaching and will collide with Earth on October

3. Though its point of impact is

unknown, the asteroid is so large that its collision will have planet-wide

effects; much, if not all, of the world’s population will be killed. Governments have enacted strict new emergency

laws as societal structures start to fall apart.

Maia, a

gigantic asteroid, is approaching and will collide with Earth on October

3. Though its point of impact is

unknown, the asteroid is so large that its collision will have planet-wide

effects; much, if not all, of the world’s population will be killed. Governments have enacted strict new emergency

laws as societal structures start to fall apart.

Maia, a

gigantic asteroid, is approaching and will collide with Earth on October

3. Though its point of impact is

unknown, the asteroid is so large that its collision will have planet-wide

effects; much, if not all, of the world’s population will be killed. Governments have enacted strict new emergency

laws as societal structures start to fall apart.

In March,

six months before Maia’s arrival, Detective Henry Palace of the Concord, New

Hampshire, police department, is called to the site of an apparent

suicide. Though new on the job, he

quickly becomes convinced that Peter Zel’s death was the result of murder, not

suicide. He continues the investigation

even though his colleagues are convinced Zel was just another “hanger” who,

like so many other people faced with possible extinction, opted to die at his

own hands.

Of course

the question at the centre of the book is “What is the point of solving cases,

even murder cases, when it seems that everyone may soon die anyway?” Many people have become “hangers” by choosing

to kill themselves; others have “gone bucket list,” leaving responsibilities to

chase their dreams. Many of those who

continue working do so only because they lack sufficient funds to financially

survive until Maia’s arrival. There are

others, however, who love their jobs and feel a sense of moral responsibility

to continue their work.

Henry falls

into this last category. He always

wanted to be a detective, and because many investigators have abandoned their positions,

Henry was promoted into his dream job. Though

he is living in a pre-apocalyptic world, he is determined to find some justice

for Peter Zel. His determination can be

admired but it comes at a great cost to others.

His investigation has a lot of collateral damage, so his insensitivity

is sometimes cruel. For instance, he

demands the coroner perform an autopsy though, as a consequence, she misses her

daughter’s music recital. People end up

losing jobs because Henry insists Peter’s boss find some files.

It is the

characterization of Henry that is a strong element in the book. He is young and inexperienced and so makes

mistakes. He is not the stereotypical great

detective; he solves the case just by being methodical. He is capable of compassion, yet at other

times is cruel in the choices he makes.

He has a tendency to be judgmental.

In other words, he is a very human protagonist.

The story

is narrated in first person point of view.

As a result, suspense is created because the reader knows only what

Henry knows. Towards the end, however,

it becomes aggravating when Henry speaks repeatedly of having figured out the

identity of the murderer, but he doesn’t reveal who it is. It’s a reality show technique where one has

to wait for the big reveal.

This is the

first of a trilogy; the other titles are Countdown

City and World of Trouble. The murder case is conclusively solved, but a

subplot involving Henry’s sister Nico is open-ended. I will definitely continue reading the

series.

Saturday, September 16, 2017

2017 National Book Award for Fiction Longlist

The

longlist for the National Book Award for Fiction was announced yesterday. There are ten titles:

Elliot

Ackerman for Dark at the Crossing

Daniel

Alarcón for The King Is Always Above the

People: Stories

Charmaine

Craig for Miss Burma

Jennifer

Egan for Manhattan Beach

Lisa Ko for

The Leavers (See my review at https://schatjesshelves.blogspot.ca/2017/05/review-of-leavers-by-lisa-ko-new-release.html.)

Min Jin Lee

for Pachinko

Carmen

Maria Machado for Her Body and Other

Parties: Stories

Margaret

Wilkerson Sexton for A Kind of Freedom

Jesmyn Ward

for Sing, Unburied, Sing

Carol Zoref

for Barren Island

The

National Book Awards are a set of annual U.S. literary awards presented to

American authors for books published in the United States during the award

year. National Book Awards are currently

given to one book (author) annually in each of four categories: fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and young

people's literature.

For the

nonfiction longlist, go to https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-national-book-awards-longlist-nonfiction-2017.

For the

poetry longlist, see https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-national-book-awards-2017-longlist-poetry.

And the

longlist for young people’s literature can be found at https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-national-book-awards-2017-longlist-young-peoples-literature.

National

Book Awards finalists will be announced on October 4, and the winners will be

announced at a ceremony in New York on November 15.

Friday, September 15, 2017

Fall Literary Festivals in Canada

We are

midway through September, and the fall literary festivals have begun. I’m fortunate enough to live where I am

within a 3-hour drive of three festivals:

the Ottawa's Writers' Festival which

takes place October 19–24, the Kingston Writers Fest which runs September 27–October

1, and The Knowlton Literary

Festival which is held between October

12–15 in Brome Lake, QC.

49th Shelf recently featured a list of fall

literary festivals across Canada. I’m

sharing it so perhaps you can find one in your part of the country: https://49thshelf.com/Blog/2017/09/07/Your-Fall-2017-Literary-Festival-Guide.

If you are

interested in festivals held throughout the year, go to https://www.writersunion.ca/canadian-festivals-and-reading-series. Here the festivals are listed by province.

Wednesday, September 13, 2017

2017 Man Booker Prize Shortlist

The

shortlist for the prestigious Man Booker Prize was revealed earlier today. There are six finalists on the list:

4321 by Paul Auster (US)

History of Wolves by Emily Fridlund (US) - See my review at https://schatjesshelves.blogspot.ca/2017/08/review-of-history-of-wolves-by-emily.html.)

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid (UK-Pakistan)

Elmet by

Fiona Mozley (UK)

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders (US) – See my

review at https://schatjesshelves.blogspot.ca/2017/08/review-of-lincoln-in-bardo-by-george.html.

Autumn by Ali Smith (UK)

The Man

Booker Prize is considered one of the leading prizes for high-quality literary

fiction written in English. This is the fourth

year that the prize has been open to writers of any nationality. The winner, who will receive £50,000, will be

announced on Tuesday, October 17, in London.

For more information about the announcement, go to http://themanbookerprize.com/news/man-booker-prize-announces-2017-shortlist.

Tuesday, September 12, 2017

Review of LOST IN SEPTEMBER by Kathleen Winter (New Release)

4 Stars

I read and

enjoyed Kathleen Winter’s debut novel, Annabel,

so I was excited to read her second novel.

I read and

enjoyed Kathleen Winter’s debut novel, Annabel,

so I was excited to read her second novel.

I read and

enjoyed Kathleen Winter’s debut novel, Annabel,

so I was excited to read her second novel.

I read and

enjoyed Kathleen Winter’s debut novel, Annabel,

so I was excited to read her second novel.

In

present-day Montreal, Jimmy, a young man who bears a striking resemblance to

General James Wolfe, visits the city for 11 days. General Wolfe died September 13, 1759, on the

Plains of Abraham in a pivotal battle in Canadian history, but Jimmy seems to

have Wolfe’s memories. In 1752, Wolfe

lost an 11-day leave in Paris because of the switch from the Julian to the

Gregorian calendar; now Jimmy takes that leave in Montreal.

The

mystery, of course, is who Jimmy is.

Surely he can’t be who he claims to be, and there are hints and clues

that suggest Jimmy is very much a contemporary man. Wolfe fought battles at Culloden and

Dettingen, but he wouldn’t have been in Ghundy Ghar which Jimmy mentions in the

first few pages. The best description of

Jimmy is as a figure on a Tarot card: “The

man does not appear to know where to go or how to move beyond loss.” At the beginning, Jimmy speaks of his

“waiting for the crater that might jolt me properly into being in the present

instead of floating in the past.” It is difficult to believe that Jimmy is Wolfe,

but it becomes clear that he is certainly a veteran damaged by his experiences

in war; he describes himself as having “no shield against reliving war in

Technicolor, all night, every day.”

Obviously,

the book focuses on the futility of war.

If a soldier were able, in the future, to return to the battlefield on

which he died, would he find that his sacrifice had been worthwhile? Wolfe won Canada for England and had believed

“there would grow a people here, out of our own little spot in England, to fill

this space and become a vast Empire, the seat of power and learning,” but Jimmy,

during a visit to Costco, concludes, “It is as if England has had a nightmare

in which the Empire’s crowning achievement has been to inflate the size of material

goods.” Wolfe hoped “boys who became

soldiers with me . . . I really thought the New World was supposed to give them

a chance at a parcel of ground” but Jimmy finds only “the old, weary bondage”

because “the poor toil here unexalted as ever.

As for the well-provided, their banal crowing echoes the clang of

trussell on planchet under every New World moment: a relentless strike of metal

into coin.” Jimmy concludes that it is “ludicrous

to call the land owned, conquered, taken by one small group of men who do not

even plan to stay on it.”

The time

and place of a war is unimportant: “I

have surveyed moor . . . desert . . . does the terrain’s name matter? Land outspans army and king. It outlives us, and will outbreathe us. Does the year of any given campaign –

Dettingen, Culloden, Quebec, Ghundy Ghar – do its dates mean a thing? I dig up human bones everywhere – no matter

where we fight a war, that land holds bones in it from previous warriors.” And history has not had a paucity of

battlefields: “’There have been a lot of

enemies in a few well-chosen hellholes.’”

The suggestion is that war and soldiers have always been with us and

always will be: “All warriors descend

from a single, ancient Council of War forged at the dawn of manhood.” It is easy to draw men into war: “How little deception is needed when men

believe so fervently in bits of bright cloth.”

And the result is always the same:

broken men.

There is

some commentary about contemporary life in la

belle province. Jimmy is aghast at

how little English he encounters since Wolfe won the country for England in

1759. In Quebec City, Jimmy sees the

monument shared by Montcalm and Wolfe and makes a telling observation: “It came to me then, that every monument,

every object in the plains museum, every rose and bleeding heart nodding its

head in the Joan of Arc garden bejewelling the Plains of Abraham, every citizen

and every ship and bird and fish in and on the river, attest to the continued life

in Quebec of the people of Wolfe and Montcalm, standing on the same ground but,

like the names on the plinth overlooking the river, never seeing each other.”

I knew

little about General James Wolfe other than what I was taught in high school Canadian

history classes so many years ago. It is

obvious that Kathleen Winter did considerable research. I advise readers to do some reading about the

man before reading the book; even the Wikipedia article would be helpful in

explaining some of the references. Look

at Benjamin West’s painting entitled “The Death of General Wolfe” (https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/beta/asset/-/MQGJPSKUj9ySHg?hl=en)

to appreciate Jimmy’s comment: “a

literary person called Margaret Atwood claimed West made me appear like a dead,

white codfish, and I had to agree.”

At first I

struggled with the book. It is sometimes

difficult to know what is real and what isn’t.

Jimmy is the narrator and his thoughts wander so a reader may find

him/herself confused at times. After

finishing the novel, I went back to the beginning and did a quick second

reading. This book is the type that

needs a re-reading to highlight Winter’s accomplishment. Images and symbols clarify themselves. The book

is not perfect because it does drag at times and some of the events are

predictable, but it has much to recommend it:

the protagonist, the setting, and the themes are all

well-developed.

Note: I received an eARC of this book from the

publisher via NetGalley.

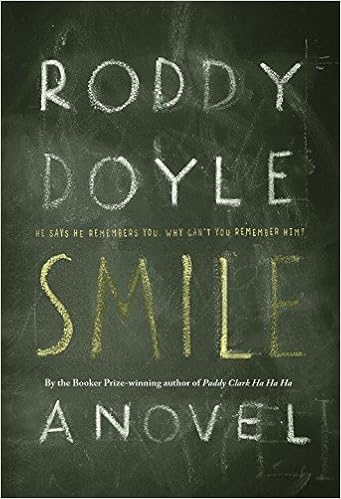

Review of SMILE by Roddy Doyle (New Release)

4 Stars

This is a

very difficult book to review without ruining it for others, but I will try my

best.

This is a

very difficult book to review without ruining it for others, but I will try my

best.

Note: I

received an eARC of the book from the publisher via NetGalley.

This is a

very difficult book to review without ruining it for others, but I will try my

best.

This is a

very difficult book to review without ruining it for others, but I will try my

best.

Victor

Forde is a middle-aged, recently divorced man who has returned to the

neighbourhood of Dublin where he grew up.

He starts going to a nearby pub where he encounters a man named Eddie

Fitzpatrick. Though Victor has no clear

memory of him, Eddie remembers Victor from secondary school; in fact, it is

surprising how much Eddie knows about Victor:

“He’d know – he knew – more than I’d want known. He’d know facts and lies.”

Victor has

an ambiguous relationship with Eddie. He

admits, “I didn’t like him. I really

didn’t like him. He made me nervous. And he bored me. I hated it when he stood too close, or when

he sat back, right in front of me, and scratched his crotch or walloped his

stomach. And I couldn’t remember

him. He’d been in school with me; I

didn’t doubt that.” One of the reasons

he dislikes Eddie is that he stirs up memories of his difficult high school

years. Nonetheless, Victor continues to

return to the pub: “The point was, I

knew we’d be meeting again and I’d done nothing to avoid it.”

Victor also

reminisces about his life after graduation, especially his meeting Rachel Carey

who became his wife. A very beautiful

woman, she became a celebrity as a television chef while Victor gained some

notoriety as a provocateur on radio talk shows.

For many years he has been writing a book about “the rot that was at the

heart of Ireland.”

There is a

great deal of mystery throughout the novel.

One of the major questions is why Victor keeps going back to the pub

knowing that Eddie may very well be there.

There is an aura of menace around Eddie; his is a threatening presence

so is it their shared experiences, like both having lost their fathers at a

young age, that are the draw? Others at

the bar even mistake them for brothers or cousins. Victor tries to explain the attraction (“But

there was something about him – an expression, a rhythm – that I recognised and

welcomed”), but it isn’t convincing. Why

is it that Eddie remembers so much about Victor but Victor’s memories are much

less clear? Why does Eddie wear the same

clothes every time he comes to the pub?

There are

other unanswered questions as well.

Victor’s attraction to Rachel is understandable, but the reader, like

one of Victor’s acquaintances, wonders “What did she see in you?” It is easy to see that Rachel was good for

Victor; he says, “She saved me and, later, she carried me. Her assertiveness . . . her willingness to

cry, the way she took sex, took and gave – I can see now that it saved me. It stunned me and made me.” The reason for the marriage break-up is also

not clarified; the only indication of a problem is Victor’s wanting to hear his

wife explain about her day: “I’ll listen this time.” And then there’s a son who is mentioned only

occasionally?

The

characterization of Victor is wonderful.

He is not a likeable person at the beginning. He admits that he was envious of others; as a

young man, he wrote music reviews and ruined careers with his scathing

reviews: “I didn’t hate [the

bands]. I envied them, and that was far

worse. They could do it, and I couldn’t. It was the start of my career, and I tore

into them.” He admits that “I was being

a prick, but it gave me power.” He also

describes himself as being rigid: “I was

inflexible – still am. I loosened a bit,

for [Rachel], but it was always a fight.

My place was mine; hers was hers.

I like order.” And he

acknowledges, “I was just angry – and vain.”

But slowly Victor gets the reader’s sympathy as we learn about his life

in school. He describes himself as a bit

of a misfit as a teenager so I found myself wishing that as an adult he would

get what he wanted from his evenings at the local pub: “companionship, the ease of it, the

acceptance.”

And then

there’s the ending! It forces the reader to reconsider everything

he/she has just read. Some may think the

ending is too shocking and unforeshadowed, but that is not true. I couldn’t resist re-reading the book and

found numerous clues I had missed on first reading. Some clues are obvious but others are

exceedingly subtle. A second reading is

really necessary to fully appreciate Doyle’s accomplishment. The ending is discomfiting but crucial in

developing the novel’s theme.

Those who

enjoy Doyle’s style – the quick dialogue, the humour, the sense of place – will

not be disappointed. I had not read

anything by Doyle since Paddy Clarke Ha

Ha Ha, but I’m ever so glad I read this book. I definitely recommend it.

Monday, September 11, 2017

One Book for Each American State

My husband

and I are planning a short trip into the U.S.

We will be concentrating on the northeastern part of the country and

visiting either New Hampshire, Vermont, or New York. Researching for the trip reminded me of an

article I read last month.

Travel and Leisure “selected the best books based in every state

by looking for titles that almost use their state as another character. The

setting is so deeply entwined with these texts, the story couldn't even exist

in another place or time.” Alabama gets To Kill a Mockingbird; Georgia, Gone with the Wind; Oklahoma, The Grapes of Wrath; Washington, Snow Falling on Cedars; and Missouri, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

If we

decide to visit New Hampshire, I need to read Frindle by Andrew Clements; if, Vermont, All the Best People by Sonja Yoerg; and if, New York, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty

Smith. I have a problem with the last

option since we will visit the state, not the city of New York.

Go to http://www.travelandleisure.com/culture-design/books/books-based-in-every-state#

to see the complete list.

Sunday, September 10, 2017

2017 Kirkus Prize Longlist

The Kirkus

Prize is a $50,000 prize sponsored by Kirkus

Reviews. Finalists are chosen from

books that earned a Kirkus Star which is given to books of “exceptional

merit.” I do not find the reviews in the

magazine to be especially thorough or insightful, tending more towards plot

summary than literary analysis. Books

that earned the Kirkus Star with publication dates between Sept. 1, 2016 to

Aug. 31, 2017 are automatically nominated for the 2017 Kirkus Prize. See the fiction list at https://www.kirkusreviews.com/prize/nominees/fiction/.

The list is

extensive; there are 423 titles on the list.

A shortlist of six should be released sometime in the near future. The winner will be announced on Nov. 2, 2017.

Here are my

reviews of the books which I have read on the longlist:

The Golden House by Salman Rushdie: https://schatjesshelves.blogspot.ca/2017/09/review-ot-golden-house-by-salman.html

The Witches of New York by Ami McKay: https://schatjesshelves.blogspot.ca/2016/10/review-of-witches-of-new-york-by-ami.html

The Essex Serpent by Sarah Perry: https://schatjesshelves.blogspot.ca/2017/01/review-of-essex-serpent-by-sarah-perry.html

Anything is Possible by Elizabeth Strout: https://schatjesshelves.blogspot.ca/2017/04/review-of-anything-is-possible-by.html

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders: https://schatjesshelves.blogspot.ca/2017/08/review-of-lincoln-in-bardo-by-george.html

Idaho by Emily Ruskovich: https://schatjesshelves.blogspot.ca/2017/01/review-of-idaho-by-emily-ruskovich-new.html

History of Wolves by Emily Fridlund: https://schatjesshelves.blogspot.ca/2017/08/review-of-history-of-wolves-by-emily.html

These are the Names by Tommy Wieringa: https://schatjesshelves.blogspot.ca/2016/12/review-of-these-are-names-by-tommy.html

Do not Say we have Nothing by Madeleine Thien: https://schatjesshelves.blogspot.ca/2016/10/review-of-do-not-say-we-have-nothing-by.html

Saturday, September 9, 2017

Trumpian Satire Courtesy of The New Yorker

I know I’ve

mentioned previously that I have a subscription to The New Yorker. I read the

print edition though I also check out the digital version almost daily. The humour section is great for providing a

few chuckles in a world where the news is relentlessly depressing.

The

Borowitz Report by Andy Borowitz is a must-read; his satire targeting Trump never

disappoints. Where else can you find pieces like “Eight Hundred Thousand People

with Dreams to Be Deported by One with Delusions” and “Obama Cruelly Taunted

Trump in Letter Riddled with Multisyllabic Words” and “Trump’s Horrific

Spelling Reassures Nation That He Cannot Correctly Enter Nuclear Codes” and “Trump

Says Sun Equally to Blame for Blocking Moon” and “Ivanka and Jared Vacationing

in Moral Vacuum”.

The most

recent issue (Sept. 11) has another wonderful piece entitled “Jared Kushner’s Harvard

Admissions Essay” written by Megan Amram:

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/09/11/jared-kushners-harvard-admissions-essay. This ranks up there with one of my other

favourites which I linked on my blog last March: “Kellyanne Conway Spins Great Works of

Literature” by Bob Vulfov: https://schatjesshelves.blogspot.ca/2017/03/kellyanne-conway-literary-critic.html

.

The New Yorker is one of Trump’s fake news outlets. What better recommendation for taking out a

subscription?!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)